__________

“Liberty

and union, now and forever, one and inseparable.”

Daniel Webster.

__________

January 26-27: Daniel Webster and Robert Hayne engage

in debate over the future of the country. Webster’s reply to Hayne is called

“the most famous Senate speech” on the U.S. Senate’s own website.

Hayne stirred Webster to respond, after insisting that the nation was a

collection of sovereign states, and, as such, each sovereign state retained the

right to “nullify” laws passed by the federal government if they infringed on

state interests.

The senator from Massachusetts offers his rebuttal:

“I

hold it to be a popular government, erected by the people.”

…It

is, Sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s government, made for the

people, made by the people, and answerable to the people. The people of the

United States have declared that the Constitution shall be the supreme law. We

must either admit the proposition, or dispute their authority. The States are,

unquestionably, sovereign, so far as their sovereignty is not affected by this

supreme law. But the State legislatures, as political bodies, however

sovereign, are yet not sovereign over the people. So far as the people have

given the power to the general government, so far the grant is unquestionably

good, and the government holds of the people, and not of the State governments.

We are all agents of the same supreme power, the people. The general government

and the State governments derive their authority from the same source. Neither

can, in relation to the other, be called primary, though one is definite and

restricted, and the other general and residuary. The national government

possesses those powers which it will be shown the people have conferred upon

it, and no more. All the rest belongs to the State governments, or to the

people themselves. So far as the people have restrained State sovereignty, by

the expression of their will, in the Constitution of the United States, so far,

it must be admitted. State sovereignty is effectively controlled….the

Constitution has ordered the matter differently. To make war, for instance, is

an exercise of sovereignty; but the Constitution declares that no State shall

make war. To coin money is another exercise of sovereign power, but no State is

at liberty to coin money. Again, the Constitution says that no sovereign State

shall be so sovereign as to make a treaty… I must now beg to ask, Sir, Whence

is this supposed right of the States derived? Where do they find the power to

interfere with the laws of the Union? Sir the opinion which the honorable

gentleman maintains is a notion founded in a total misapprehension, in my

judgment, of the origin of this government, and of the foundation on which it

stands. I hold it to be a popular government, erected by

the people; those who administer it, responsible to the people; and itself

capable of being amended and modified, just as the people may choose it should

be. It is as popular, just as truly emanating from the people, as the State

governments. It is created for one purpose; the State governments for another.

It has its own powers; they have theirs. There is no more authority with them

to arrest the operation of a law of Congress, than with Congress to arrest the

operation of their laws. We are here to administer a Constitution emanating

immediately from the people, and trusted by them to our administration. It is

not the creature of the State governments. It is of no moment to the argument, that

certain acts of the State legislatures are necessary to fill our seats in this

body. That is not one of their original State powers, a part of the sovereignty

of the State. It is a duty which the people, by the Constitution itself, have

imposed on the State legislatures; and which they might have left to be

performed elsewhere, if they had seen fit. So they have left the choice of

President with electors; but all this does not affect the proposition that this

whole government, President, Senate, and House of Representatives, is a popular

government. ... The people, then, Sir, erected this government. They gave it a

Constitution, and in that Constitution they have enumerated the powers which

they bestow on it…They have made it a limited government. They have defined its

authority. They have restrained it to the exercise of such powers as are

granted; and all others, they declare, are reserved to the States or the

people. But, Sir, they have not stopped here. If they had, they would have

accomplished but half their work. No definition can be so clear, as to avoid

possibility of doubt; no limitation so precise, as to exclude all uncertainty.

Who, then, shall construe this grant of the people? Who shall interpret their

will, where it may be supposed they have left it doubtful? ... This, Sir, was

the first great step. By this the supremacy of the Constitution and laws of the

United States is declared. The people so will it. No State law is to be valid

which comes in conflict with the Constitution, or any law of the United States

passed in pursuance of it. But who shall decide this question of interference?

To whom lies the last appeal? This, Sir, the Constitution itself decides also,

by declaring, “That the judicial power shall extend to all cases arising under the

Constitution and laws of the United States.” These two provisions cover the

whole ground.

John Bach McMaster notes that there was a

time when the schoolboys (as least in the North) could recite many of Webster’s

lines from speeches:

“Our

country, our whole country, and nothing but our country.”

“Thank

God. I, I also, am an American.”

“Liberty

and union, now and forever, one and inseparable.”

*

THE DEMAND for furs, in 1830, was

growing, helping to spur the westward expansion of the United States.

The

high-crowned fur hat had long been a status symbol in Europe; and there was an

enormous demand for beaver pelts. The Mountain Men filled the demand. “It was,”

Time-Life explains, “an incredibly hard life, lonely and perilous, and

it demanded a degree of self-reliance rarely found even among Indians. Its

appeal was its independence.”

*

MCMASTER also has this to say, as Americans continue their westward advance:

[The Great Plains] were not

entirely uninhabited. Over them wandered bands of Indians mounted on fleet

ponies; white hunters and trappers, some trapping for themselves, some for the

great fur companies; and immense herds of buffalo, and in the south herds of

wild horses. The streams still abounded with beaver. Game was everywhere, dear,

elk, antelope, bears, wild turkeys, prairie chickens, and on the streams wild

ducks and geese. Here and there were villages of savage and merciless Indians.

(97/344)

NOTE TO TEACHERS: McMaster’s last sentence passes as history in 1907. Typing this in the era of “critical race theory,” one wonders if history is ever entirely real, since historians have their own biases.

|

Photo from blogger's collection.

The Plains tribes have no idea what is coming. |

*

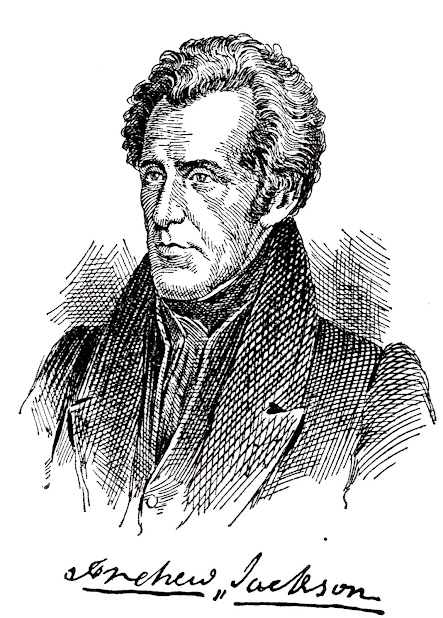

HALLECK gives us a good view of Daniel Webster. We place his story in 1830, when he

gave one of his greatest speeches:

In Webster’s youth, a

stilted, unnatural style was popular for set speeches. He was himself

influenced by the prevailing fashion, and we find him writing to a friend:

“In my

melancholy moments I presage the most dire calamities. I already see in my

imagination the time when the banner of civil war shall be unfurled; when

Discord’s hydra form shall set up her hideous yell, and from her hundred mouths

shall howl destruction through our empire.”

Such unnatural prose

impresses us to-day as merely an insincere play with words, but in those days

many thought a stilted, ornate style as necessary for an impressive occasion as

Sunday clothes for church. An Oratorical Dictionary for the

use of public speakers, was actually published in the first part of the

nineteenth century. This contained a liberal amount of sonorous words derived

from the Latin, such as “campestral,” “lapidescent,” “obnubilate,” and

“adventitious.” Such words were supposed to give dignity to spoken utterance. …

Webster was cured of such

tendencies by an older lawyer, Jeremiah Mason, who graduated at Yale about the

time Webster was born. Mason, who was frequently Webster’s opponent, took

pleasure in ridiculing all ornate efforts and in pricking rhetorical bubbles.

Webster says that Mason talked to the jury “in a plain conversational way, in short

sentences, and using no word that was not level to the comprehension of the

least educated man on the panel. This led me to examine my own style, and I set

about reforming it altogether.” Note the simplicity in the following sentences

from Webster’s speech on The Murder of Captain Joseph White:

“Deep sleep had fallen on

the destined victim, and on all beneath his roof. A healthful old man, to whom

sleep was sweet, and the first sound slumbers of the night held him in their

soft but strong embrace. ... The face of the innocent sleeper is turned from

the murderer, and the beams of the moon, resting on the gray locks of his aged

temple, show him where to strike.”

In his speech on The

Completion of the Bunker Hill Monument, we find the following paragraph,

containing two sentences which present in simple language one of the great

facts in human history:

“America has furnished to

the world the character of Washington! And if our American institutions had

done nothing else, that alone would have entitled them to the respect of

mankind.”

He knew when illustrations and

figures of rhetoric could be used to advantage to impress his hearers. In discussing

the claim made by Senator Calhoun of South Carolina that a state could nullify a

national law, Webster said:

“To begin with

nullification, with the avowed intent, nevertheless, not to proceed to

secession, dismemberment, and general revolution, is as if one were to take the

plunge of Niagara, and cry out that he would stop half way down.”

To show the moral bravery

of our forefathers and the comparative greatness of England, at that time, he

said:

“On this question of

principle, while actual suffering was yet afar off, they raised their flag

against a power, to which, for purposes of foreign conquest and subjugation,

Rome, in the height of her glory, is not to be compared; a power which has

dotted over the surface of the whole globe with her possessions and military

posts, whose morning drumbeat, following the sun, and keeping company with the

hours, circles the earth with one continuous and unbroken strain of the martial

airs of England.”

For nearly a generation

prior to the Civil War, schoolboys had been declaiming the peroration of his

greatest speech, his Reply to Hayne (1830):

“When my eyes shall be

turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining

on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States

dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or

drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood!”

This peroration brought Webster as an invisible

presence into thousands of homes in the North. The hearts of the listeners

would beat faster as the declaimer continued:

“Let

their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the

republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced,

its arms and trophies streaming in their original luster, not a stripe erased

or polluted, nor a single star obscured….”

When the irrepressible

conflict came, it would be difficult to estimate how many this great oration

influenced to join the army to save the Union. The closing words of that

speech, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” kept

sounding like the voice of many thunders in the ear of the young men, until

they shouldered their muskets.

*

AS NEW YORK CITY grows, it is decided

that a line of omnibuses should be started.

|

Uber - before Uber was invented. |

*

June 30: Robert

E. Lee’s mother had been an invalid, requiring his care, after he graduated

from West Point.

Now,

his new bride, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, great granddaughter of Marth

Washington, by her first husband, also proved sickly.

She was careless in her personal

apparel to the point of untidiness. Her domestic management was complemented

when it was termed no worse than negligent. In her engagements she was

forgetful and habitually late, an aggravating contrast to the minute-promptness

of her husband. Despite these shortcomings and later a nervous whimsicality

that sometimes puzzled him, she held the love of Robert Lee through life.

Ministering, rather than ministered unto, his first thought was always of her.

She accepted this as her due from “Mr. Lee” as she called him, and even after

the War between the States, when he was a demigod in the eyes of the South, she

ordered him about. Yet rarely was a woman more fully a part of her husband’s

life. This, fundamentally was because of his simplicity and her fineness of

spirit. She was interested in people and in their happiness. (22/28)

*

August 28: With

the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad now in operation, proponents of the new form

of transportation stage a race between a horse pulling a car and a locomotive

pulling the same load.

The

horse loses.

*

MCMASTER describes the state of transportation in the United States at that time,

including the battle between advocates of canal vs. rail travel:

Passengers traveled on the canal in

packet boats, as they were called. The hull of such a craft was eighty feet

long and eleven feet wide, and carried on its deck a long, low house with flat

roof and sloping sides. In each side were a dozen or more windows with green

blinds and red curtains. When the weather was fine, passengers sat on the roof,

reading, talking, or sewing, till the man at the helm called “Low bridge!” when

everybody would rush down the steps and into the cabin, to come forth once more

when the bridge was passed. Walking on the roof when the packet was crowded was

impossible. Those who wished such exercise had to take it on the towpath. Three

horses abreast could drag a packet boat some four miles an hour.

While the means of travel were

improving, the inns and towns even along the great stage routes had not

improved. “When you alight at a country tavern,” said a traveler, it is ten to

one you stand holding your horse, bawling for the hostler while the landlord

looks on. Once inside the tavern every man, woman, and child plies you with

questions. To get a dinner is the work of hours. At night you are put into a

room with a dozen others and sleep two or three in a bed. In the morning you go

outside to wash your face and then repair to the barroom to see your face in

the only looking glass the tavern contains.”

These early railroads were made of

wooden beams resting on stone blocks set in the ground. The upper surface of

the beams, where the wheels rested, was protected by long trips or straps of

iron spiked to the beam. The spikes often worked loose, and, as the car passed

over, the strap would curl up and come through the bottom of the car, making

what was called a “snake head.” …

Locomotives could not climb steep

grades. When a hill was met with, the road had to go around it, or if this was

not possible, the engine had to be taken off and the cars pulled up or let down

an inclined plane by means of a rope and stationary engine. … When all the cars

of the train had been pulled up in this way, they would be coupled together and

made fast to a little puffing, wheezing locomotive without cab or brake, whose

tall smokestack sent forth volumes of wood smoke and red-hot cinders.

The friends of canals [attacked the new

railroads]. Snow, it was said, would block them for weeks. If locomotives were

used, the sparks would make it impossible to carry hay or other things

combustible. The boilers would blow up as they did on steamboats. Canals were

therefore safer and cheaper. (97/304-307)

*

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA, Jefferson had,

in 1819, introduced a code of discipline meant to be enforced by students.

This radical

experiment proved ill-suited to conditions at the University, for the students

were too young and too undisciplined to operate such a code. Within six months

after the University opened, the system broke down, as students disrupted

classes, assaulted professors and rioted. In the face of these disorders, which

brought threats of resignation from the professors, who had been recruited in

Europe with great difficulty, a rigid set of rules under faculty enforcement

was established. Monroe was not present at the board meeting when the new

disciplinary code was drafted, but he was placed on a committee with Chapman

Johnson to draw up a new plan of government for the University. Collecting data

from other institutions – including West Point, which had experienced severe

disciplinary problems – he submitted a report to the Board of Visitors in 1830.

Monroe began

his report by observing that the government of a university was not unlike

parental authority and must be so organized as to ensure that the students

applied themselves to their studies, attended lectures and showed respect

toward the professors. Moreover, they must be restrained from dissipation,

drinking, gaming and frequenting taverns. (24/552-553)

|

University of Virginia. |

.jpg)

.JPG)