.jpg) |

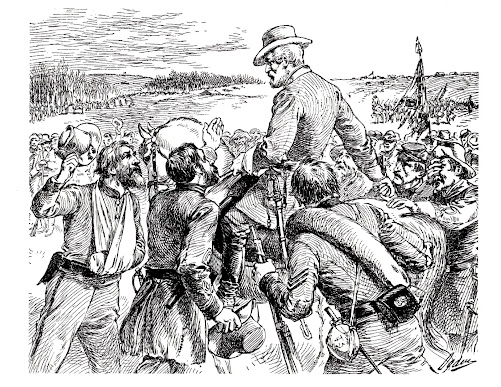

Surrender at Appomattox. |

__________

“My

World is now divided – where Yankees are

and

where Yankees are not.”

Mary

Boykin Chesnut

__________

Van Loon describes Lincoln as a man “who during four lonely and terrible years had learned how to fight without hating.” (124-398)

Andrews writes of his

travails, “The War President trod at no time a path of flowers.” (4/179)

*

By this time, Confederate finances were in shambles. In December 1861, Benjamin Andrews writes, it took $120 in paper money to buy $120 in gold. Two years later it took $1,900 and by 1864, the figure was $5,000.

Before

the war was over a pound of sugar brought $75, a spool of thread was $20. Toward

the end of the war a Confederate soldier, just paid off, went into a store to

buy a pair of boots. The price was $200. He handed the storekeeper a $500 bill.

“I can’t change this.” “Oh, never mind,” replied the paper millionaire. “I

never let a little matter like $300 interfere with a trade.” Of course when the

Confederacy collapsed all this paper money became absolutely worthless. (4/175)

Henry Kyd Douglas remembers paying

ridiculous sums in Confederate money for necessities. He gave $9.75 for two

mint juleps. Why not $10.00 he wondered. A uniform cost him $1,500, a horse

worth $250 in gold went for $5,800. A joke has a cavalryman offered $5,000 for

his broken down horse. He scoffs. “Five thousand for this horse! Why, I gave a

thousand dollars this morning for currying him!”

“The Confederate soldier was then

serving his country for less than forty cents a month in gold; he was virtually

fighting without pay, without bounty, and with no expectation of a pension. Pay

day became a sarcasm and a jest.” (20/262)

*

General Grant spends the winter of 1864-1865, gradually extending his lines at Petersburg. “He had,” Andrews writes, “a death-grip upon the Confederacy’s throat, and waited with confidence for the contortions which should announce its death.”

Continuous fighting

had drained the South of able fighting men. “Boys from fourteen to eighteen,

and old men from forty-five to sixty, were also pressed into service as junior

and senior reserves, the Confederacy thus, as General Butler wittily said, “robbing

both the cradle and the grave.” (4/120, 121)

*

January 19: General John Pegram, 33, marries Hetty Cary, 28, a Richmond socialite. The wedding is attended by a number of Confederate generals, as well as President Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina.

One onlooker said of the

bride that the “happy gleam of her beautiful brown eyes seemed to defy all

sorrow.”

|

Hetty Cary. Photo from internet. |

*

February

6: Men die uselessly in the final days

of any war, particularly if they’re fighting for the losing side. Henry Kyd

Douglas was present when “General Pegram was shot through the body near the

heart. I jumped from my horse and caught him as he fell and with assistance

took him from his horse. He died in my arms, almost as soon as he touched the

ground.”

The battle soon ended and the

question – who would go tell his new wife – faced the officers.

Major New went on this unenviable duty and I took the General’s body back to my room at Headquarters. An hour after, as the General lay, dead, on my bed, I heard the ambulance pass just outside the window, taking Mrs. Pegram back to their quarters. New had not seen her yet and she did not know; but her mother was with her. A fiancée of three years, a bride of three weeks, now a widow!

NOTE TO TEACHERS: I think it would work

to ask students to write down what they think would have been Hetty’s thoughts

after hearing her husband was already dead. It might even be better to have her

write, after Lee’s army surrenders – with his sacrifice having been in vain.

*

February 17: Having turned north after taking Savannah, on this day, Sherman’s troops capture Columbia, South Carolina – where the legislature of that state first announced its decision to secede from the Union. The destruction wreaked on the city is extensive, and a fire spreads out of control.

Who struck the first match, is still in

doubt.

Many of the Yankees got drunk

before starting the rampage. Union General Henry

Slocum observed: “A drunken soldier with a musket in one hand

and a match in the other is not a pleasant visitor to have about the house on a

dark, windy night.” Sherman claimed that the raging fires were started by

evacuating Confederates and fanned by high winds. He later wrote: “Though I

never ordered it and never wished it, I have never shed any tears over the

event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for, the end of

the War.”

What is not in doubt: Two-thirds of

the town was reduced to ashes.

The following song, published in

1865, and written by Henry Clay Work, follows the exploits of General Sherman

and his men.

Marching through Georgia

Bring the good ol’ Bugle boys! We’ll sing another song,

Sing it with a spirit that will start the world along,

Sing it as we used to sing it fifty thousand strong,

While we were marching through Georgia.

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

How the darkeys shouted when they heard the joyful sound,

How the turkeys gobbled which our commissary found,

How the sweet potatoes even started from the ground,

While we were marching through Georgia.

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

Yes and there were Union men who wept with joyful tears,

When they saw the honored flag they had not seen for years;

Hardly could they be restrained from breaking forth in

cheers,

While we were marching through Georgia.

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

“Sherman’s dashing Yankee boys will never reach the coast!”

So the saucy rebels said and ‘twas a handsome boast

Had they not forgot, alas! to reckon with the Host

While we were marching through Georgia.

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

So we made a thoroughfare for freedom and her train,

Sixty miles in latitude, three hundred to the main;

Treason fled before us, for resistance was in vain

While we were marching through Georgia.

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

*

March

29: Mary Boykin Chesnut captures the

coming collapse of the Confederacy, writing, “My World is now divided – where

Yankees are and where Yankees are not.

*

April 2-3: An attack by Union forces irrevocably shatters Lee’s Petersburg lines.

Lee at once telegraphed to President Davis that Petersburg and Richmond must be immediately abandoned.

It was Sunday, and the

message reached Mr. Davis in church. He hastened out with pallid lips and

unsteady tread. A panic-stricken throng was soon streaming from the doomed

city. Vehicles let for one-hundred dollars an hour in gold. The state prison-guards

fled and the criminals escaped. A drunken mob surged through the streets,

smashing windows and plundering shops. General Ewell blew up the iron-clads in

the river and burned bridges and storehouses. The fire spread till one third of

Richmond was in flames. The air was filled with a “hideous mingling of the

discordant sounds of human voices – the crying of children, the lamentations of

women, the yells of drunken men – with the roar of the tempest of flame, the

explosion of magazines, the bursting of shells.” Early on the morning of the 3d

was heard the cry, “The Yankees are coming!” Soon a column of blue-coated

troops poured into the city, headed by a regiment of colored cavalry, and the Stars

and Stripes presently floated over the Confederate capital. (IV, 123-125)

|

Rebel soldier killed in Petersburg lines on April 2. The war was over a week later. Photo from internet. |

Andrews writes that

2,750,000 men were called into service by the Union, “The largest number

serving at any one time being 1,000,516 on May 1, 1865.” The Confederates

called to action 1,250,000. The greatest number at any one time the Rebels ever

mustered was 690,000 on January 1, 1863. (IV, 131)

*

“No haversack, all cartridge box.”

April 9: Lee’s hungry, tattered army is forced to surrender at Appomattox Court House, Va.

Henry Kyd Douglas jokes that for a

long time the Confederate soldier’s outfit had been “no haversack, all

cartridge box.” (20-313)

He would never forget the surrender

at Appomattox:

As my decimated and ragged band with

their bullet-torn banner marched to its place, someone in the blue line broke

the silence and called for three cheers for the last brigade to surrender. It

was taken up all about him by those who knew what it meant. But for us this

soldierly generosity was more than we could bear. Many of the grizzled veterans

wept like women, and my own eyes were as blind as my voice was dumb. Years have

passed since then and time mellows memories, and now I almost forget the keen

agony of that bitter day when I recall how that line of blue broke its

respectful silence to pay such a tribute, at Appomattox, to the little line in

grey that had fought them to the finish and only surrendered because it was

destroyed. (20-319)

Douglas rode home in May 1865, on

parole, passing through Charlottesville, Waynesboro and Lexington.

As I rode through the latter place

late one afternoon, I was halted with a shout, and Buck stood in the street by

my side; he began a rapid explanation of what he had done. Fearing that I would

be sent to prison and remembering my injunction as to the hand trunk and

papers, he had determined to escape through the lines with my spare horse, my

hand trunk, and all he could carry. He swam the James River at night near Amherst

Court House, crossed the mountain and arrived safely in Lexington. There he

intended to wait awhile for me. If he could hear nothing from me and the war

went on, he intended, as he said, to “cut his way through to General Johnston”

– which it was supposed General Lee was trying to do. My horse was at pasture

out in the country and my hand trunk was hidden in a hole in the cellar under

the woodpile and everything in it was safe.

(20-320)

Douglas had attended Franklin and

Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa, graduating in 1859. He was wounded six

times during the war.

*

April 14: John Wilkes Booth shoots President Abraham Lincoln, who dies in the morning of April 15.

The historian Allan Nevins describes Lincoln, in an undated article saved from American Heritage, “Roosevelt in History: An Appraisal,” on FDR.

Of Lincoln, he writes:

His public utterances…attest [to] a rare

intellectual power. The wisdom of his principle public acts, his magnanimity

toward all foes public and private, his firmness under adversity, his elevation

of spirit, his power of strengthening the best purposes and suppressing the

worst instincts of a broad, motley democracy, place him in the front rank of

modern statesman.

When eighteen, he went to Tennessee,

where he married and was taught to read and write by his wife. He was a man of

ability, and was three years alderman and three years mayor of Greenville… In

1875 he was again elected United States senator, but died the same year.

(97-loose page)

*

Walt Whitman’s poem is an elegy for the fallen leader, the sad song of “the gray-brown bird” symbolic of the nation’s sorrow, says Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker, June 24, 2019.

He says he went online to listen

to the “melancholy arpeggio” of the hermit thrush.

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d

When lilacs last in the dooryard

bloom’d,

And the great star early droop’d

in the western sky in the night,

I mourn’d, and yet shall mourn

with ever-returning spring.

Ever-returning spring, trinity

sure to me you bring,

Lilac blooming perennial and drooping

star in the west,

And thought of him I love.

2

O powerful western fallen

star!

O shades of night—O moody,

tearful night!

O great star disappear’d—O the

black murk that hides the star!

O cruel hands that hold me

powerless—O helpless soul of me!

O harsh surrounding cloud that

will not free my soul.

3

In the dooryard fronting an old

farm-house near the white-wash’d palings,

Stands the lilac-bush

tall-growing with heart-shaped leaves of rich green,

With many a pointed blossom

rising delicate, with the perfume strong I love,

With every leaf a miracle—and

from this bush in the dooryard,

With delicate-color’d blossoms

and heart-shaped leaves of rich green,

A sprig with its flower I

break.

4

In the swamp in secluded

recesses,

A shy and hidden bird is

warbling a song.

Solitary the thrush,

The hermit withdrawn to himself,

avoiding the settlements,

Sings by himself a song.

Song of the bleeding

throat,

Death’s outlet song of life,

(for well dear brother I know,

If thou wast not granted to sing

thou would’st surely die.)

5

Over the breast of the spring,

the land, amid cities,

Amid lanes and through old

woods, where lately the violets peep’d from the ground, spotting the gray

debris,

Amid the grass in the fields

each side of the lanes, passing the endless grass,

Passing the yellow-spear’d

wheat, every grain from its shroud in the dark-brown fields uprisen,

Passing the apple-tree blows of

white and pink in the orchards,

Carrying a corpse to where it

shall rest in the grave,

Night and day journeys a

coffin.

6

Coffin that passes through lanes

and streets,

Through day and night with the

great cloud darkening the land,

With the pomp of the inloop’d

flags with the cities draped in black,

With the show of the States

themselves as of crape-veil’d women standing,

With processions long and

winding and the flambeaus of the night,

With the countless torches lit,

with the silent sea of faces and the unbared heads,

With the waiting depot, the

arriving coffin, and the sombre faces,

With dirges through the night,

with the thousand voices rising strong and solemn,

With all the mournful voices of

the dirges pour’d around the coffin,

The dim-lit churches and the

shuddering organs—where amid these you journey,

With the tolling tolling bells’

perpetual clang,

Here, coffin that slowly

passes,

I give you my sprig of

lilac.

7

(Nor for you, for one

alone,

Blossoms and branches green to

coffins all I bring,

For fresh as the morning, thus

would I chant a song for you O sane and sacred death.

All over bouquets of

roses,

O death, I cover you over with

roses and early lilies,

But mostly and now the lilac

that blooms the first,

Copious I break, I break the sprigs

from the bushes,

With loaded arms I come, pouring

for you,

For you and the coffins all of

you O death.)

8

O western orb sailing the

heaven,

Now I know what you must have

meant as a month since I walk’d,

As I walk’d in silence the

transparent shadowy night,

As I saw you had something to

tell as you bent to me night after night,

As you droop’d from the sky low

down as if to my side, (while the other stars all look’d on,)

As we wander’d together the

solemn night, (for something I know not what kept me from sleep,)

As the night advanced, and I saw

on the rim of the west how full you were of woe,

As I stood on the rising ground

in the breeze in the cool transparent night,

As I watch’d where you pass’d

and was lost in the netherward black of the night,

As my soul in its trouble

dissatisfied sank, as where you sad orb,

Concluded, dropt in the night,

and was gone.

9

Sing on there in the swamp,

O singer bashful and tender, I

hear your notes, I hear your call,

I hear, I come presently, I

understand you,

But a moment I linger, for the

lustrous star has detain’d me,

The star my departing comrade

holds and detains me.

10

O how shall I warble myself for

the dead one there I loved?

And how shall I deck my song for

the large sweet soul that has gone?

And what shall my perfume be for

the grave of him I love?

Sea-winds blown from east and

west,

Blown from the Eastern sea and

blown from the Western sea, till there on the prairies meeting,

These and with these and the

breath of my chant,

I’ll perfume the grave of him I

love.

11

O what shall I hang on the

chamber walls?

And what shall the pictures be

that I hang on the walls,

To adorn the burial-house of him

I love?

Pictures of growing spring and

farms and homes,

With the Fourth-month eve at

sundown, and the gray smoke lucid and bright,

With floods of the yellow gold

of the gorgeous, indolent, sinking sun, burning, expanding the air,

With the fresh sweet herbage

under foot, and the pale green leaves of the trees prolific,

In the distance the flowing

glaze, the breast of the river, with a wind-dapple here and there,

With ranging hills on the banks,

with many a line against the sky, and shadows,

And the city at hand with

dwellings so dense, and stacks of chimneys,

And all the scenes of life and

the workshops, and the workmen homeward returning.

12

Lo, body and soul—this

land,

My own Manhattan with spires, and

the sparkling and hurrying tides, and the ships,

The varied and ample land, the

South and the North in the light, Ohio’s shores and flashing Missouri,

And ever the far-spreading

prairies cover’d with grass and corn.

Lo, the most excellent sun so

calm and haughty,

The violet and purple morn with

just-felt breezes,

The gentle soft-born measureless

light,

The miracle spreading bathing

all, the fulfill’d noon,

The coming eve delicious, the

welcome night and the stars,

Over my cities shining all, enveloping

man and land.

13

Sing on, sing on you gray-brown

bird,

Sing from the swamps, the

recesses, pour your chant from the bushes,

Limitless out of the dusk, out

of the cedars and pines.

Sing on dearest brother, warble

your reedy song,

Loud human song, with voice of

uttermost woe.

O liquid and free and

tender!

O wild and loose to my soul—O

wondrous singer!

You only I hear—yet the star

holds me, (but will soon depart,)

Yet the lilac with mastering

odor holds me.

14

Now while I sat in the day and

look’d forth,

In the close of the day with its

light and the fields of spring, and the farmers preparing their crops,

In the large unconscious scenery

of my land with its lakes and forests,

In the heavenly aerial beauty,

(after the perturb’d winds and the storms,)

Under the arching heavens of the

afternoon swift passing, and the voices of children and women,

The many-moving sea-tides, and I

saw the ships how they sail’d,

And the summer approaching with

richness, and the fields all busy with labor,

And the infinite separate

houses, how they all went on, each with its meals and minutia of daily

usages,

And the streets how their

throbbings throbb’d, and the cities pent—lo, then and there,

Falling upon them all and among

them all, enveloping me with the rest,

Appear’d the cloud, appear’d the

long black trail,

And I knew death, its thought,

and the sacred knowledge of death.

Then with the knowledge of death

as walking one side of me,

And the thought of death

close-walking the other side of me,

And I in the middle as with

companions, and as holding the hands of companions,

I fled forth to the hiding

receiving night that talks not,

Down to the shores of the water,

the path by the swamp in the dimness,

To the solemn shadowy cedars and

ghostly pines so still.

And the singer so shy to the

rest receiv’d me,

The gray-brown bird I know

receiv’d us comrades three,

And he sang the carol of death,

and a verse for him I love.

From deep secluded

recesses,

From the fragrant cedars and the

ghostly pines so still,

Came the carol of the

bird.

And the charm of the carol rapt

me,

As I held as if by their hands

my comrades in the night,

And the voice of my spirit

tallied the song of the bird.

Come lovely and soothing

death,

Undulate round the world,

serenely arriving, arriving,

In the day, in the night, to

all, to each,

Sooner or later delicate

death.

Prais’d be the fathomless

universe,

For life and joy, and for

objects and knowledge curious,

And for love, sweet love—but praise!

praise! praise!

For the sure-enwinding arms of

cool-enfolding death.

Dark mother always gliding near

with soft feet,

Have none chanted for thee a

chant of fullest welcome?

Then I chant it for thee, I

glorify thee above all,

I bring thee a song that when

thou must indeed come, come unfalteringly.

Approach strong

deliveress,

When it is so, when thou hast

taken them I joyously sing the dead,

Lost in the loving floating

ocean of thee,

Laved in the flood of thy bliss

O death.

From me to thee glad

serenades,

Dances for thee I propose

saluting thee, adornments and feastings for thee,

And the sights of the open

landscape and the high-spread sky are fitting,

And life and the fields, and the

huge and thoughtful night.

The night in silence under many

a star,

The ocean shore and the husky

whispering wave whose voice I know,

And the soul turning to thee O

vast and well-veil’d death,

And the body gratefully nestling

close to thee.

Over the tree-tops I float thee

a song,

Over the rising and sinking

waves, over the myriad fields and the prairies wide,

Over the dense-pack’d cities all

and the teeming wharves and ways,

I float this carol with joy,

with joy to thee O death.

15

To the tally of my soul,

Loud and strong kept up the

gray-brown bird,

With pure deliberate notes

spreading filling the night.

Loud in the pines and cedars

dim,

Clear in the freshness moist and

the swamp-perfume,

And I with my comrades there in

the night.

While my sight that was bound in

my eyes unclosed,

As to long panoramas of

visions.

And I saw askant the

armies,

I saw as in noiseless dreams

hundreds of battle-flags,

Borne through the smoke of the

battles and pierc’d with missiles I saw them,

And carried hither and yon

through the smoke, and torn and bloody,

And at last but a few shreds

left on the staffs, (and all in silence,)

And the staffs all splinter’d

and broken.

I saw battle-corpses, myriads of

them,

And the white skeletons of young

men, I saw them,

I saw the debris and debris of

all the slain soldiers of the war,

But I saw they were not as was

thought,

They themselves were fully at

rest, they suffer’d not,

The living remain’d and

suffer’d, the mother suffer’d,

And the wife and the child and

the musing comrade suffer’d,

And the armies that remain’d

suffer’d.

16

Passing the visions, passing the

night,

Passing, unloosing the hold of

my comrades’ hands,

Passing the song of the hermit

bird and the tallying song of my soul,

Victorious song, death’s outlet

song, yet varying ever-altering song,

As low and wailing, yet clear

the notes, rising and falling, flooding the night,

Sadly sinking and fainting, as

warning and warning, and yet again bursting with joy,

Covering the earth and filling

the spread of the heaven,

As that powerful psalm in the

night I heard from recesses,

Passing, I leave thee lilac with

heart-shaped leaves,

I leave thee there in the

door-yard, blooming, returning with spring.

I cease from my song for

thee,

From my gaze on thee in the

west, fronting the west, communing with thee,

O comrade lustrous with silver

face in the night.

Yet each to keep and all,

retrievements out of the night,

The song, the wondrous chant of

the gray-brown bird,

And the tallying chant, the echo

arous’d in my soul,

With the lustrous and drooping

star with the countenance full of woe,

With the holders holding my hand

nearing the call of the bird,

Comrades mine and I in the

midst, and their memory ever to keep, for the dead I loved so well,

For the sweetest, wisest soul of

all my days and lands—and this for his dear sake,

Lilac and star and bird twined

with the chant of my soul,

There in the fragrant pines and

the cedars dusk and dim.

*

THE HISTORIAN Allan Nevins describes Lincoln, in an undated article saved from American Heritage, “Roosevelt in History: An Appraisal,” on FDR. Of Lincoln, he writes:

His public utterances…attest [to] a rare intellectual power. The wisdom of his principle public acts, his magnanimity toward all foes public and private, his firmness under adversity, his elevation of spirit, his power of strengthening the best purposes and suppressing the worst instincts of a broad, motley democracy, place him in the front rank of modern statesman.

*

June 19: The last slaves in Texas receive the news. The war is over. They are free at last. This “Juneteenth” becomes a day of celebration.

Starting in 2022, the day will become a national holiday.

*

June: The Rebel cruiser, Shenandoah, unaware of the ending of the war continues on her way to Australia, destroying “seven of our merchantmen. She then went to Bering Sea and in one week captured twenty-five whalers, most of which she destroyed. … In August a British ship captain informed the commander of the Shenandoah that the Confederacy no longer existed. (97/ page number missing)

*

“Send us

our wages for the time we served you.”

August 7: Four months after the Civil War ended, a now former slave owner, Colonel P. H. Anderson wrote to his old slave, Jourdon Anderson. He asked him to return to the plantation to work. The “Negro,” as then called, had moved to Ohio where he found work for pay, and supported his family.

Jourdon replied in a letter of his own:

Dayton, Ohio,

August 7, 1865

To My Old Master, Colonel P.H.

Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Sir: I got your letter and was glad to

find you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and

live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I

have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you

long before this for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they

never heard about your going to Col. Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that

was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I

left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still

living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again and see Miss

Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them

all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I

would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville

Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me Henry intended to shoot me if he

ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the

good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here; I get

$25 a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,

—the folks here call her Mrs. Anderson),—and the children—Milly, Jane and

Grundy—go to school and are learning well; the teacher says Grundy has a head

for a preacher. They go to Sunday-School, and Mandy and me attend church

regularly. We are kindly treated; sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them

colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they

hear such remarks, but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to

Col. Anderson. Many darkies would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you

master. Now, if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be

better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can

have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in

1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy

says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you are sincerely

disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your

sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This

will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and

friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years and

Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a

week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and

eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages has been kept

back and deduct what you paid for our clothing and three doctor’s visits to me,

and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice

entitled to. Please send the money by Adams Express, in care of V. Winters,

Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past we

can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker

has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me

and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense.

Here I draw my wages every Saturday night, but in Tennessee there was never any

pay-day for the Negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there

will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter please state

if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up and

both good-looking girls. You know how it was with Matilda and Catherine. I

would rather stay here and starve, and die if it comes to that, than have my

girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters.

You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored

children in your neighborhood, the great desire of my life now is to give my

children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

P.S. — Say howdy to George Carter, and

thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson

Source: Reprinted in Lydia Maria Child, The Freedmen’s Book (Boston: Tickenor and Fields, 1865), 265-67.

Suffrage: the right to vote

Mississippi elected sheriffs – but even

in areas heavily African American all sheriffs were white. Students should

realize how hopeless it might be to approach white officers

*

In his descriptions of the postwar Era, Andrews reveals his inherent prejudices time and again. In this passage he seems particularly clueless:

Great numbers of Confederates came home to find their farms sold

for unpaid taxes, perhaps mortgaged to ex-slaves. The best Southern land, after

the war, was worth but a trifle of its old value. Their ruin rendered many

insane; in multitudes more it broke down all energy. The braver spirits – men

to whom till now all toil had been strange – set to work as clerks,

depot-masters and agents of various business enterprises. High-born ladies,

widowed by Northern bullets, became teachers or governesses. In the

comparatively few cases where families retained their estates, their effort to

keep up appearances was pathetic. One by one domestics were dismissed; dinner

parties grew rare; stately coaches lost their paint and became rickety;

carriage and saddle horses were worn out at the plow and replaced by mules. At

last the master learned to open his own gates, the mistress to do her own

cooking. (11/113)

“It was difficult to get help on the plantation,” he adds, “so immersed in politics and so lazy had the field hands become.” (11/113)

(Excuse this blogger

while he gags at that last sentence.)

|

The Confederate soldier returns to a ruined land. And has to do the work slaves used to do for nothing! |

Andrews also explained: “How angry the conflict was will appear when we see that it brought the ‘scalawag,’ the ‘carpet-bagger,’ and the negro, partly each by himself and partly together, into radical collision with all that was most solid, intelligent and moral in Southern society.” (11/114)

He does admit that there were some “perfectly honest carpet-baggers,” who viewed their task as almost missionary work. (11/117)

Others, he labels “cunning sharks.” (11/118)

*

Claude G. Bowers’ book, The Tragic Era, written in 1928, is racist garbage, masquerading as history, but revealing in all the wrong ways.

Slavery and the aftermath of slavery don’t concern him, save for the damage the end of the “Peculiar Institution” has on the South. “That the Southern people literally were put to the torture is vaguely understood,” he says, describing the Reconstruction Era. But by “Southern people,” he means white Southerners.

Unless I missed it, he goes on for more than 500 pages, and not once expresses any sympathy for the freed slaves. 105/Preface

A typical Bowers’ scene:

“The long rows of grinning negro slaves.”

Any one familiar with the Washington of the previous decade, with its lordly leisure and aristocratic elegance, would scarcely have recognized, in the city of the summer of 1865, the town he had known before. Society was dull, the doors of the finer houses closed. The long rows of grinning negro slaves had disappeared from the streets…Droves of strange negroes, flocking in from the South, laughing uproariously, and a bit too conscious of their freedom, jostled the pedestrians on the streets. The martial tread of army officers resounded on the pavements, and sharp-faced, furtive-eyed speculators and gamblers were seen everywhere, and women of indifferent morality, soon to become familiar to the capital, had already begun their march upon the town with much swishing of skirts. 105/9

Bowers never sheds a tear for the slaves, or notes their suffering, but paints a tragic picture of the postwar South:

“A degree of destitution that would draw pity from a stone.”

For some time now a straggling

procession of emaciated, crippled men in ragged gray had been sadly making their

way through the wreckage to homes that in too many instances were found to be

put piles of ashes. These men had fought to exhaustion. For weeks they would be

found passing wearily over the country roads and into the towns, on foot and

horseback. It was observed that “they are so worn out that they fall down on

the sidewalks and sleep.” The countryside through which they passed presented

the appearance of an utter waste, the fences gone, the fields neglected, the

animals and herds drive away, and only lone chimneys marking the spots where

once had stood merry homes. A proud patriarch lady riding between Chester and

Camden in South Carolina scarcely saw a living thing, and “nothing but tall

blackened chimneys to show that any man had ever trod this road before”; and

she was moved to tears at the funeral aspect of the gardens where roses were

already hiding the ruins. The long thin line of gray-garbed me, staggering from

weakness into towns, found them often gutted wit the flames of incendiaries or

soldiers. Penniless, sick at heart and in body, and humiliated by defeat, they

found their families in poverty and despair. “A degree of destitution that

would draw pity from a stone,” wrote a Northern correspondent. Entering the

homes for a crust or cup of water, they found the furniture marred and broken,

dishes cemented “in various styles” and with “corn cobs substituting for

spindles in the looms.” The houses of the most prosperous planters were found

denuded of almost every article of furniture, and in some sections women and

children accustomed to luxury begged from door to door. 105/45-46

Bowers is not focused on the “destitution” of the freed slaves, of course, who have nothing and have always had nothing.

He continues.

“The one hope for the restoration of the cities was resumption of normal activities in the country, the cultivation of the plantations as of old.” One master of a Mississippi plantation returned home to find only a few mules and one cow still remained. 105/46

But the gravest problem

of all was that of labor, for the slaves were free and were demanding payment

in currency that their old masters no longer possessed. The one hope of staving

off starvation the coming winter was to persuade the freedmen to work on the

share, or wait until the crops were marketed for their pay. Many old broken

planters called their former slaves about them and explained, and at first many

agreed to wait for their compensation on the harvest. Many of them went on

about their work, “very quiet and serious and more obedient and kind than they

had ever been known to be.” It was observed that with the pleasure of knowing

they had their freedom there was a touch of sadness. Some Northerners, who had

taken Mrs. Stowe’s novel too literally, were amazed at the numerous “instances

of the most touching attachment to their old masters and mistresses.” One of

these was touched one Sunday morning when the negroes appeared in mass at the

mansion house to pay their respects. “I must have shaken hands with four

hundred,” she wrote. Something of the beautiful loyalty in them which guarded

the women and children with such zeal while husbands and fathers were fighting

far away persisted in the early days of their freedom. Old slaves, with fruit

and gobblers and game, would sneak into the house with an instinctive sense of

delicacy and leave them in the depleted larder surreptitiously. Occasionally

some of these loyal creatures, momentarily intoxicated with the breath of

liberty, would roam down the road toward the towns, only to return with

childlike faith to the old plantation. 105/47

“Quite soon,” says Bowers, “an extravagant notion of proper compensation for services was to turn the freedman adrift. Soon they were drunk with a sense of their power and importance.”

Former owners, meeting negroes born on their plantations and addressing them in the familiar way, were sharply rebuked with the assurance that they no longer responded to that name. “If you want anything, call for Sambo,” said a patronizing old freedman. “I mean call me Mr. Samuel, dat my name now.” Had the intoxication of the new freedom worked no more serious changes in the negro’s character, all would have been well, but he was to meet with influences designed to separate him in spirit from those who understood him best. 105/48

Freedom – it meant

idleness, and gathering in noisy groups In the streets. Soon they were living

like rats in ruined houses, in miserable shacks under bridges built with refuse

lumber, in the shelter of ravines and in caves in the banks of rivers. Freedom

meant throwing aside all marital obligations, deserting wives and taking new

ones, and in an indulgence in sexual promiscuity that soon took its toll in the

victims of consumption and venereal disease. Jubilant, and happy, the negro who

had his dog and a gun for hunting, a few rags to cover his nakedness, and a

dilapidated hovel in which to sleep, was in no mood to discuss work. 105/49

Bowers can’t even figure out why

a freed slave, after twenty or thirty years of unpaid labor, might have nothing

more than “a few rags,” and a “dilapidated hovel” to his name. Really, his book

is terrible.

No comments:

Post a Comment