.jpg) |

Custer's Last Stand - fanciful depiction. Painting from the internet. |

____________________

“Greed and avarice on the part of the Whites in other words, the Almighty Dollar, is at the bottom of nine tenths of all our Indian troubles.”

General George Crook

____________________

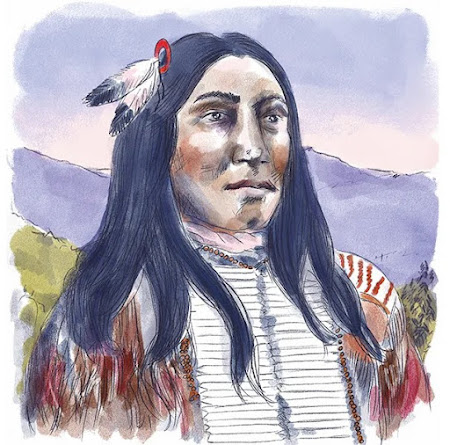

CRAZY HORSE understands, by 1876, that the Lakota way of life is under threat. The buffalo hide trade is booming, but the herds are already diminishing. According to one Lakota historian, Crazy Horse

was a

surprisingly humble man. He was an introvert prone to low moods and self-doubt,

who dressed plainly and shied away from social gatherings and did not

participate in the Lakota ritual waktoglakapi, in which warriors

recounted their exploits. Such reticence makes him something of an elusive

figure, for all his fame. Indeed, he sometimes seemed to think that he was good

at little else besides warfare, as Marshall found by collecting oral histories and

scouring archives. Oglalas considered him a great general, but he never donned

the war bonnet, the honorific feathered headgear worn by military leaders,

which he would have deserved many times over.

By the time Crazy Horse met Custer, he

had been fighting the encroachments of the settlers for over a decade. Eleven

years earlier, he had been asked to join the elite Shirt Wearers Society, “dedicated

to protecting the welfare of the Oglala tribe.” He and his warriors had blocked

railroad surveys, and he had fought in the Battle of Red Buttes, the Fetterman Fight,

and the Wagon Box Fight. He was also respected as a leader who gladly gave up

almost all his possessions to others, and fearless in battle.

|

Artist rendering - Smithsonian magazine. |

*

January 31: Angered by white encroachments on their

lands, the Lakota and Cheyenne begin leaving their reservation and resume raids

on settlements and travelers. A deadline is set for this date, by the

commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for them return by this date or be

treated as hostiles.

*

March 2:

Secretary of War William Belknap races to the White House, turns in his

resignation, and bursts into tears. He is hoping to forestall an impeachment

vote in the House of Representatives that same day. The vote advances, and his trial

begins in May.

*

May: The impeachment trial of William Belknap begins, and dominates business in the Senate.

A former Iowa state legislator and Civil

War general, Belknap had held his cabinet post for nearly eight years. In the

rollicking era that Mark Twain dubbed the Gilded Age, Belknap was famous for

his extravagant Washington parties and his elegantly attired first and second

wives. Many questioned how he managed such a grand lifestyle on his $8,000

government salary.

During the trial, one senator declares that he has heard the taunt, even from friendly lips, “that the only product of the United States’ institutions in which she surpassed all other nations beyond question was her corruption.” (11/201)

Caleb P.

Marsh, one of a firm of contractors in New York City, testified before a

Congressional Committee that, in 1870, Belknap had offered him the control of

the post-tradership at Fort Sill, Indian Territory, for the purpose of enabling

him to extort from the actual holder of the place, one John S. Evans, $3,000

four times a year as the price of continuing in it. The Secretary and his

family appeared to have received $24,450 in this way. Belknap’s resignation was

offered and accepted a few hours before the House passed a unanimous vote to

impeach him. Other dubious acts of Belknap’s came to light. Notably a contract

for erecting tombstones in national cemeteries, from which, as was charged, he

realized $90,000. (11/202)

*

Congress once again (see: 1874) moves

to end the indiscriminate slaughter of the buffalo herds.

National Geographic explains:

… when the bill was debated again, Representative

James Throckmorton of Texas summed up the administration’s de facto policy with

stark precision: There is no question that, so long as there are millions of

buffaloes in the West, so long the Indians cannot be controlled, even by the

strong arm of the government. I believe it would be a great step forward in the

civilization of the Indians and the preservation of peace on the border if

there was not a buffalo in existence.” (NG 11-1994, p. 71) (See: 1882.)

Buffalo Bill Cody certainly did his

part, killing 4,280 bison in a stretch of only 18 months (69)

|

Pile of buffalo skulls. Photo from the internet. |

*

An article in American Heritage

from the 50s or 60s is titled, tellingly, “The Redskin Who Saved the White

Man’s Hide,” about Chief Washakie of the Shoshone or Snake tribe. In June,

General George Crook was advancing his troops, even though Crazy Horse had

warned that “every soldier who crossed the Tongue River would die.” His column

was protected by Crow and Shoshone scouts.

Crook is said to have lost 59 killed

and wounded; and Crazy Horse supposedly said later that he had 6,500 men under

arms at the Battle of the Rosebud.

Washakie led a large segment of his

tribe from 1850 on.

An industrious hunter and trapper

himself, Washakie encouraged his people to collect furs and make robes beyond

their own needs and trade with the whites for guns and ammunition, tools,

cloth, and ornaments. To follow his eagle-feather standard became a desirable

thing among the Shoshone people. His admission standards were high. Treaty-breakers,

horse thieves, and pilferers (that is, of white men’s property) were kept out. Washakie

made his own rules and was judge, jury, and very often executioner for those

who failed to obey. Even during one very trying period, when it looked as

though he were going to lose part of his following to certain firebrands in the

tribe, he kept his policy of stern justice and peace with the whites. He was

beginning to give aid and protection to the increasing stream of settlers who

were destroying and running off the game as they passed through to the West. …

He wanted a permanent home where his

people could learn agriculture and livestock raising. He wanted them to have

churches, and schools where they could learn to compete in a new way of life.

When asked his choice of a reservation site, he always answered that he wanted

the “Warm,” or Wind River, Valley at the eastern foot of the Wind River Mountains.

(54)

The Crows also wanted the area; and

when Crow raiding parties struck Shoshone villages, Washakie sent warning to

their chief: “I’m looking for you. When we meet I will cut out your heart and

eat it before you own braves.”

Washakie and his warriors met a

strong war party of Crows in front of a sheer butte at the north end of the Wind

River Valley. There was a pitched battle. In the middle of the fight Washakie

located the chief and drove his war horse toward him through the melee. The

Crow saw him coming and shouted a challenge. They met was a shock that unhorsed

them both and they fought on the ground with knives. Though Washakie was

considerably older than his adversary, the Crow soon lay dead at his feet.

Some insist that Washakie did eat his

enemies heart; others deny it. The Shoshone leader said later that in the heat

of battle a man “sometimes does things that he is sorry for afterward,” but

otherwise said he did not remember. Two white men said they witnessed him

carrying a heart, impaled on his lance, the day after the battle. This fight at

Crow Heart Butte ended the wars between the two tribes. (109)

Washakie later asked for Christian

missionaries to come to the Shoshone reservation and spread the Word.

In 1878, a large party of Arapaho

pitched a village on Shoshone land, with the agreement of white officials.

Washakie protested, but also understood their plight. They were starving and

their children were suffering. He made it plain:

I don’t like these people; they eat their

dogs. They have been the enemies of the Shoshones since before the birth of the

oldest old men. If you leave them here there will be trouble. But it is plain

that they can go no further now. Take them down to where the Popo Agie walks

into the Wind River and let them stay until the grass comes again. But when the

grass comes again take them off my reservation. I want my words written down on

paper with the white man’s ink. I want you all to sign as witnesses to what I

have said. And I want to copy of that paper. I have spoken.

The Arapaho never left; and in

January 1937, after a long court battle, the Shoshone were awarded $4.5 million

in damages. “With the accrued interest from the original claim and additional

claims,” the writer for American Heritage said, a bit too cheerfully,

“this has grown to a tremendous sum.” (110)

Washakie died, age 90 or more, on

February 21, 1900. He was buried with military honors, “rank of Captain.” Troop

E of the First U.S. Cavalry did honors at the burial site, as white and red

mourners watched. One of the ministers who presided, Rev. Sherman Coolidge, was

a full-blooded Arapaho.

*

An alarming number of political scandals.

An alarming number of political scandals tainted the federal government in these years. One of those scandals ensnared the Secretary of War, among others.

The historian McLaughlin writes:

…the articles of impeachment were

brought by the House against William W. Belknap, the Secretary of War. He was

charged with receiving bribes, and there was no doubt of his guilt. To escape

conviction he hastily resigned his office, and then denied that the Senate had

the right to consider charges against a person who was no longer a “civil

officer of the United States.”

He was still tried; but acquitted in

part on those grounds.

Just at the close of Grant’s first

administration Congress passed an act increasing the salary of the President,

members of Congress, and other officers. It provided that the President should

receive fifty thousand dollars instead of half that sum, as heretofore, and

that members of Congress should receive seven thousand five hundred dollars

instead of five thousand dollars. This Congress was nearly at an end, but

regardless of that fact, the act declared that its members should receive the

increased salary for the two years just closing.” Andrew C. McLaughlin; A History of the American Nation; pp.

490-492; (1911).

*

May 10: The Philadelphia Centennial

Exhibition opens, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the

birth of the nation. Andrews notes that “Wagner had composed a Centennial March

for the occasion. Whittier’s Centennial Hymn was sung by a chorus of 1,000

voices. The restored South sang the praises of the Union in the words of Sidney

Lanier, the Georgia poet.” Visitors entered through 106 gates, and gasped at

the wonders found in various buildings, particularly the Main Building, 1,880

feet long, 460 wide, 70 high. “The products of all climates, tribes, and times

were here crowded together under one roof.” The Exhibition, “made Americans

realize as never before the wealth, intelligence, and enterprise of their

native country and the proud station she had taken among the nations of the

earth.”

In

Machinery Hall, for example, industrialization was on display, and “with

infinite clatter and roar, thousands of iron slaves worked their master’s will.” The Titan of all, was the Corliss engine,

built by George H. Corliss of Providence, R. I. which supplied power to all the

exhibits.

A modern Samson, dumb as well as

blind, it’s massive limbs of shining steel moved with voiceless grace and

utmost apparent ease, driving the miles of shafting and the thousands of

connected machines. The cylinders were forty inches in diameter; the piston-stroke,

ten feet. The great walking-beams, nine feet wide in the center, weighed eleven

tons each. The massive fly-wheel, thirty feet in diameter, and weighing fifty-six

tons, made thirty-six revolutions a minute. The whole engine, with the strength

of 1,400 horses, weighed 700 tons.

“The great West,” he adds, “with its

monster steam-ploughs and threshing machines, placed before the eye the farming

methods of a race of giants.” All that summer, Andrews wrote, visitors, “found

their way to this shrine of the world’s progress.” (IV 301-309)

NOTE TO TEACHERS: I wonder if students have such an optimistic view of machine progress, or human progress in general.

*

__________

“I expect that Custer was crazy enough to believe he could win, being the type of man who carries the whole world within his own head and thus when his passion is aroused and floods his mind, reality is utterly drowned.”

Thomas Berger

__________

Plenty Coups is chosen to be the chief of the Crow people. In the false hope that allying with the whites will help them in the fight against their traditional enemies, the Lakota and Cheyenne, the Crow ally with the whites. In June, six Crow warriors join Custer to serve as scouts.

Remembering

having talked to an old wise man, when he was young, Plenty Coups will look

back sadly and remark, “Here I am, an old man, sitting under this tree just

where that old man sat seventy years ago when this was a different world.”

*

June 25: George Armstrong Custer is killed

in a battle with Sioux and Cheyenne warriors and the Seventh Cavalry is mauled.

Newspaper writers will call for retribution, and Sitting Bull and his people

will pay a high price for their victory in the end.

This painting by the Native American

artist, T.C. Cannon, could be used to start a great discussion with students.

It is titled, simply: “Soldiers.”

NOTE TO

TEACHERS: I think this would be an excellent picture to simply show students

and ask them to write out and then share their reactions.

|

Painting from the internet. |

*

Benjamin Andrews’ take on the Battle of the Little Big Horn, writing in 1896, is interesting (if inaccurate), and clearly biased. He notes that Reno and his men were attacked and held at bay, “being besieged in all more than twenty-four hours.”

Meantime,

suddenly coming upon the lower end of the Indians’ immense camp, the gallant Custer

and his braves, without an instant’s hesitation, advanced into the jaws of

death. That death awaited every man was at once evident, but at the awful

sensation, the sickening horror attending the realization of that fact, not a

soul wavered. Balaklava was pastime to this, for here not one “rode back.” All

that was left of them, after perhaps twenty-five minutes, was so many mostly

unrecognizable corpses.

Andrews quotes a source here, but I’m not sure who it is:

“Two hundred and sixty-two were with Custer, and two hundred and sixty-two died overwhelmed. With the last shot was silence. The report might been written: ‘None wounded; none missing; all dead.’ No living tongue of all that heroic band was left to tell the story.”

The historian then picks up the tale:

Finding himself outnumbered twelve or

more to one – the Indians mustered about 2,500 warriors, besides a caravan of

boys and squaws- Custer had dismounted his heroes, who, planting themselves

mainly on two hills some way apart, the advanced one held by Custer, the other

by captains Keogh and Calhoun, prepared to sell their lives dearly. The

redskins say that had Reno maintained the offensive they should have fled, the

chiefs having, at the first sight of Custer, ordered camp broken for this purpose.

But when Reno drew back this order was countermanded, and the entire army of

the savages was concentrated against the doomed Custer. By waving blankets and

uttering their hellish yells, they stampeded many of the cavalry horses, which

carried off precious ammunition in their saddlebags. Lining up just behind a

ridge they would rise quickly, fire at the soldiers, and drop, exposing

themselves little, but drawing Custer’s fire, so causing additional loss of

sorely needed bullets. The whites’ ammunition spent, the dismounted savages

rose, fired, and whooped like the demons they were; while the mounted ones,

lashing their ponies, charged with infinite venom, overwhelming Calhoun and

Keogh, and lastly Custer himself. Indian boys pranced over the fields on ponies,

scalping and re-shooting the dead and dying. At the burial many a stark visage

wore a look of horror. “Rain-in-the-Face,” who mainly inspired and directed the

battle on the Indian side, boasted that he cut out and ate Captain Tom Custer’s

heart. Most believe that he did so. “Rain-in-the-Face” was badly wounded, and

used crutches ever after. Brave Sergeant Butler’s body was found by itself,

lying on a heap of empty cartridge shells which told what he had been about.

Sergeant Mike Madden had a leg mangled

while fighting, tiger-like, near Reno, and for his bravery was promoted on the

field. He was always over-fond of grog, but long abstinence had now intensified

his thirst. He submitted to amputation without anesthesia. After the operation

the surgeon gave him a stiff horn of brandy. Emptying it eagerly and smacking

his lips, he said: “M-eh, Doctor, cut off the other leg.”

Andrews absolves Custer, for the most part:

His surprise lay not in finding Indians

before him, but in finding them so fatally numerous. Some of General Terry’s

friends charged Custer with transgressing his orders in fighting as he did.

That he was somewhat careless, almost rash, in his preparations to attack can

perhaps be maintained, though good authority declares the “battle fought tactically

and with intelligence” on Custer’s part, and calls it unjust to say that he was

reckless or foolish. Bravest of the brave, Custer was always anxious to

fight…But that he was guilty of disobedience to his orders is not shown.

It, indeed, came quite directly from

General Terry that had Custer lived to return “he would at once have been put

under arrest and court martialed for disobedience.” (11/187-190)

Andrews sums up:

Small as was Custer’s total force, yet

had Reno supported him as had been expected, the fight would have been a

victory, the enemy killed, captured, driven down upon Gibbon, or so cut to

pieces as never to have reappeared as a formidable force. In either of these

cases, living or dead, Custer would have emerged from the campaign with undying

glory and there would have been no thought of a court-martial or of censure.

(11/193)

|

Custer's fight - based on historical evidence. |

|

Sitting Bull. Both of the above found online. |

The Little Bighorn Battlefield brochure includes a few useful details. Custer, with five companies (C, E, F, I and L) rides to his doom with about 210 men. Reno and Benteen lose 53 killed and 52 wounded.

The Northern Cheyenne Chief Two Moon recalled that shooting was quick, quick. Pop-pop-pop very fast. Some of the soldiers were down on their knees, some standing. … The smoke was like a great cloud, and everywhere the Sioux went the dust rose like smoke. We circled all around him – swirling like water around a stone. We shoot, we ride fast, we shoot again. Soldiers drop, and horses fall on them.”

The National Park Service estimate is that 7,000 Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho were camped on the Little Bighorn River that day, including 1,500 to 2,000 warriors. Evidence gathered soon after the battle, and even by archaeologists since, indicates that a sizeable number of Custer’s men advanced down Medicine Tail Coulee. They are hoping to strike the Indian village across a ford but are turned back. At one point, Company C charged the massed warriors attacking from the east. Lame White Man led a counterattack that drove them back, although he was later killed. Lt. James Calhoun and Company L make a second stand, but Gall, Crow King, Lame White Man, Two Moons and others stampede the cavalry horses, which are being held in a nearby ravine. Captain Myles Keogh and I Company try to hold off attackers next. Crazy Horse and White Bull overwhelm the retreating soldiers. Custer and “approximately 41 men shoot their horses for breastworks and make a last stand.”

The natives remove their own dead, estimated to be 60-100, “and place them in tipis and on scaffolds and hillsides.”

In 1890, the U.S. Army erects 249 headstone markers to show where soldiers fell.

In 1999, the National Park Service begins

placing red granite markers where Cheyenne and Lakota warriors were known to

fall.

*

June 25

(Part 2): William O. Taylor,

from Troy, New York, was a four-year veteran of service with the Seventh Cavalry

when Custer met Sitting Bull and his warriors in battle. Records show Taylor was

five feet one-half inch tall. He would survive the campaign but be mustered out

of the army on 1/17/77. He complete his memoir on the Custer Massacre in 1917.

(With Custer on the Little Bighorn)

Taylor would later talk about

comrades who were “mustered out” on that fateful day of combat.

Two lines of a poem he penned:

No boots and spurs, no hat or gun, no

uniform had they,

But bare as on their natal day the

poor hacked bodies lay.

“Conflicts grew out of our bad faith.”

Taylor was sympathetic to the tribes

– knowing, for example, that the Sioux had signed a treaty in 1851,

guaranteeing $50,000 per year for fifty years. The Senate, he quotes “amended

the treaty by limiting appropriations to ten years” without notifying the natives.

He says conflicts “grew out of our bad faith.” He goes back to the Northwest

Ordinance, which declares that the “utmost good faith shall always be observed

toward the Indians, their lands and property shall never be taken from them

without their consent, and in their property, rights, and liberty they shall

never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful war authorized by

Congress.”

On March 17, he writes, an expedition led by Gen. Crook struck a village of Crazy Horse and destroyed 105 lodges, killing several, “capturing a large herd of horses. The horses were, however, soon retaken by the Indians.”

Bitter weather sent the troops back to the forts, but both sides understood that all-out warfare was coming.

Taylor explains the motivation behind

Custer’s fateful behavior. President Grant had tried to block him from

participating in the three-pronged expedition planned for June, after Custer

testified against former Secretary of War Belknap during his impeachment.

…that General Custer had been deeply

humiliated in his own eyes and those of his brother officers, is equally true.

So that when he started on the expedition he was stung to the quick. And it can

easily be imagined by anyone who knew the man that, if given the slightest

opportunity he would not hesitate to take the greatest of risks to redeem

himself. (76/11)

Custer, with Gen. Alfred Terry’s

approval (who was scheduled to lead one of the three forces that would try to trap

the Sioux and Cheyenne in the summer), forwarded a letter to Grant, ending with

a plea, “that while not allowed to go in command of the expedition I may be

permitted to serve with my regiment in the field. I appeal to you as a Soldier

to spare me the humiliation of seeing my regiment march to meet the enemy and I

not to share its dangers.” Terry supported his request, saying, “Lieutenant

Colonel Custer’s services would be very valuable with his regiment.” (76/13)

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, then

head of the U.S. Army, agreed to let Custer take command, but warned Terry:

“Advise Custer to be prudent, not to take along any newspaper men, who always

make mischief, and to abstain from personalities in the future.” (76/14)

Taylor notes that Troops G, H and K, of the Seventh Cavalry, had only recently “received a large number of recruits, fresh from civil life.” (76/17)

The Custer expedition (Gen. Crook led the third force) carried large supplies

of forage and rations, with 114 six-mule teams, 37 two-mule teams, and 35 pack

mules, with 179 teamsters. At 5 a.m. on May 17 a trumpeter sounded, “General,”

the signal to strike tents. Libby Custer and Mrs. James Calhoun went with the

troops on the first day’s march, riding at the head of the regiment. Libby

would later write that “my heart entirely failed me” as she passed wives and

children of the men lined up to watch the troops depart: “Mothers, with

streaming eyes held their little ones out at arms’ length for one last look at

the departing father.” The regimental band struck up, “The Girl I left Behind

Me.” (76/19)

Taylor quotes General Alfred Sully on

first seeing the Badlands in 1864: “Gentlemen, it looks like the bottom of Hell,

with the fires out.” (76/21)

On June 10, Major Marcus Reno with

six troops and a Gatling gun, went ahead on a scout. Seven days later, the

soldiers came across an abandoned village site; several “graves were despoiled

by the soldiers. One body, that gave forth a very offensive odor, was taken

down and pitched into the river.” (This is now the site of Miles City.)

In another abandoned village site

they “suddenly came upon a human skull lying under the remnants of an extinct

fire.” Buttons and bits of blue uniform indicated the victim was a cavalryman.

The skull seemed to have been there for months. “All the circumstances went to

show that the skull was that of some poor mortal who had been a prisoner in the

hands of savages, and who doubtless had been tortured to death, probably burned.”

The editor of Taylor’s manuscript says

the Sioux believed the human soul would be trapped if they buried their dead. (76/24)

“For his sake I wish he had not.”

Taylor refuses to condemn Custer for

ignoring orders to be careful, saying only, “that for his sake I wish he had

not.”

Custer sent Libby a letter on June

22; he had found a village of 380 lodges. He was sorry his scouts had not

followed up the trail but had turned back instead. “I fear their failure to

follow up the Indians has imperiled our plans by giving the village an intimation

of our presence. Think of the valuable time lost, but I feel hopeful of

accomplishing great results.” His Crow scouts, however, “said they had heard

that I never abandoned a trail; that when my food gave out I ate mule. That was

the kind of man they wanted to fight under. They were willing to eat mule too.”

|

Custer and his wife, Libbie, during the Civil War. Photo from the internet. |

At 3 a.m. on June 23 the regiment was awakened by the stable guard, rather than by bugle call. The troops would move at 5 a.m.

On June 24, Taylor notes, “The trail was growing fresher

every mile and the whole valley was scratched up by trailing lodgepoles. Our

interest grew in proportion as the trail freshened and there was much

speculation in the ranks as to how soon we should overtake the apparently

fleeing enemy.” (76/26-27)

The men ate a simple meal of hardtack

and coffee; after a hard day of marching, that evening they camped in a beautiful spot, with “wild

rosebushes in full bloom.” Taylor’s Troop A was close to Custer’s tent. “I was

lying on my side, facing him, and was it my fancy, or the gathering twilight

that made his face take on an expression of sadness that was new to me.” He

heard the officers singing: “Annie

Laurie,” “Little Footsteps, Soft and Gentle,” and “The Good Bye at the Door.” Then they finished with the “Doxology: Praise God from Whom all

Blessings Flow.” That last, he said, was “a rather strange song for

Cavalrymen to sing on an Indian trail.” Several young officers were fresh out

of West Point. “But as the last words died away, as if to throw off their

gloomy feelings they added ‘For He’s a

Jolly Goodfellow, That Nobody Can Deny.’” At ten that evening “we were

awakened and ordered to saddle up for a night march.”

Not far from this spot, Taylor noted, “the brave

and unconquered” Lame Deer “would soon give up his life for the right to live

and hunt along this rose-bordered steam.” (76/31)

Greg Martin, who edited Taylor’s

story, says Lame Deer was killed while trying to surrender in May 1877.

Taylor notes the “occasional bray of

some mule in the pack train” punctuated the night. “You see something like a

black shadow moving in advance.” He heard the jingle of carbines and

sling-belts. Occasionally, some soldier struck a match to light a pipe. The

flash would pierce the gloom “like a huge firefly.” Then darkness again. The

regiment halted at 2 a.m. and saddles were removed. Many of the soldiers took

the opportunity to nap. “Those who did not care to sleep sat around in little

groups discussing the prospects of a fight and pulling away at the ever present

pipe.” (76/32)

NOTE TO TEACHERS: It might be fun to

have kids imagine what the troops were talking about in those early morning

hours.

Their march took them past

another abandoned teepee, which was set on fire by the scouts. Inside was the

body of Old She Bear, killed a few days

earlier in a fight with Gen. Crook and his men. The Little Bighorn was “a stream some

fifty to seventy five feet wide, and from two to four feet deep of clear, icy

cold water.” Taylor let his horse drink. “I took off my hat and, shaping the

brim into a scoop, leaned over, filled it and drank the last drop of water I

was to have for twenty-four long hours.” The men dismounted and tightened their

saddle girths. Looking back at one point, he saw Reno “just taking a bottle

from his lips. He then passed it to Lieutenant Hodgson. It appeared to be a

quart flask, and about one half or two thirds full of an amber colored liquid.”

On the morning of June 25 the men

counted off, the fours being given the job of holding horses, if that became

necessary.

Taylor tried to trade places with a

trooper named Cornelius Crowley, who had lately shown signs of mental disorder.

“To most of us it was our first real battle at close range.”

Reno and his men were ordered to

charge the eastern end of the big Sioux and Cheyenne village. “Over sage and

bullberry bushes, over prickly pears and through a prairie dog village without

a thought we rode. A glance along the line shows a lot of set, determined

faces.” “The Death Angel was very near,” Taylor knew. “To most of us it was our

first real battle at close range.” (76/35-37)

They quickly realized they were in a

tough spot, facing off against a much larger force of enemy warriors. They were

driven back, and Taylor and others rode into a patch of woods along the river,

hoping to find cover. He watched large numbers of Sioux and Cheyenne moving

among the trees, apparently hoping to cut off the soldier’s retreat. One

warrior “wore a magnificent war bonnet of great long feathers encircling his

head and hanging down his back, the end trailing along the side of his pony. I

did want to take a shot at him but the trees were close together, and I was not

a very good marksman.” More and more warriors swarmed around Reno and his men.

Taylor spoke of “a whooping, howling mass of the best horsemen, the most cruel

and fiercest fighters in all our country, or any other.” They were “shouting

and racing toward the soldiers, most of whom were seeing their first battle,

and many, of whom I was one, had never fired a shot from a horse’s back.”

Taylor’s right stirrup was nearly ripped off by a branch and he had trouble

keeping his seat. “I can not say that I did much execution, but I tried to,

firing at an Indian directly opposite who I thought was paying special

attention to myself.”

Once the order to retreat came,

Taylor and the rest of Reno’s men tried to cross the Little Big Horn and reach higher

ground. In trying to leap the riverbank he lost his revolver. “I saw a

struggling mass of men and horses,” with the blood of the dead and wounded “coloring

the water near them. Lieutenant Hodgson was one of the number and had just been

wounded, so I heard him say.” Taylor’s mount was totally exhausted, a sorry

horse to begin, nicknamed “Steamboat,” because of the tired puffing he made

when traveling. (76/38, 41-42)

“Why don’t we move?”

Reno lost his hat on the way up a

steep bluff where he and his men formed a defensive position; he wrapped a red

handkerchief round his head. Captain Frederick Benteen and the regiment’s pack

train joined them around 2:30 p.m., having had a message delivered by Sgt.

David C. Kanipe of Tom Custer’s Troop C, calling on them to come quick to join

the battle. They can hear firing in the distance and many men wondered, “Why

don’t we move?” “All of the officers must have known that Custer was engaged

with the Indians and quite near for he had not time to go a great way.”

Twelve more men managed to struggle

up the bluffs around 4:30, having been hiding in the woods. (Two others stayed behind, afraid to risk being seen. They were later discovered by the Sioux and killed.) A member of Troop A

found Taylor’s horse and returned him. “Not an article of my equipment or

belongings was missing although the horse had been for nearly three hours quite

near, if not within the Indian line.” Later still, on the evening of June 26,

four more men, Lt. Charles De Rudio, Pvt. Tom O’Neill, Frank Gerard (Taylor

spells his name “Girard”), who served as an interpreter to Custer’s Indian

scouts, and William Jackson, a scout, would escape from the woods, “after many

narrow escapes and an absence of about thirty four hours.” (76/49)

All day, on the 25th, firing from the Indians continued,

dying slowly at dusk, “ceasing altogether about nine o’clock.” A bugler was

sent to a nearby hill to sound calls, “Taps” being played, although it normally

“sounded over the grave of a soldier at the time of his burial.” (76/51)

A defensive wall was built in one

spot, made of boxes of hardtack, packsaddles and even sides of beef and dead

horses and mules. Taylor and six men were posted on picket duty. Taylor took

his two-hour turn, sitting in the sagebrush, rather than walking around, and

making himself a target. “The shouting and sound of the drums in the camps of

the Indians could still be heard.”

“To defend all that he had in life.”

He imagines: “In many a lodge lay a

cold red form brought from the near by field of battle, the lifeless form of a

husband and father who had rode out so bravely but a few hours before to defend

all that he had in life, his wife and children, and a little skin covered lodge.”

At some point that night the sound of a bugle could be heard in the distance,

which brought the men to their feet, “But it was not an army call that I had

ever heard or was familiar with at least.”

The sound seemed to stir the Sioux

and Cheyenne. The drums beat louder, and Taylor could hear an “outburst of

wolf-like yells.” When his time on guard was up, he found “the soldier’s couch,

the rough hard ground,” and was soon fast asleep. (76/53-54)

When the sun rose again on June 26, the

soldiers pinned atop the bluff continued to strengthen their defenses. Taylor

was ordered to help build a defensive wall for Benteen’s position. He was

carrying a box of hardtack on his shoulder “when a bullet crashed into the

box.” “I had some doubts about every finishing the trip, short as it was. But I

did and unharmed.” Resuming his own position, he said a civilian packer named

Frank Mann, just to his left, stuck up his head to see what was going on and

took a bullet “right between the eyes.” “Life seemed very attractive throughout

that eventful day…and I think most of the soldiers felt that unless a special

providence interfered we were certainly doomed.” (76/58)

The soldiers dug in, carving out

rifle pits with room for six or eight men. “Our tools were tin cups and plates,

knives, sharpened paddles made out of pieces of hardtack boxes, and a few

shovels.”

A number of men volunteered to go

down to the river for water. Michael Madden of Troop K was hit in the leg and

had to have it amputated.

On the morning of the June 27, the

natives having abandoned their village and fled, Taylor remembered, the soldiers

could be seen “eating in peace our breakfast of bacon, hardtack and coffee. We

watered our horses who acted as if they would never get enough, washed our

faces and hands and straightened ourselves up generally.” (76/60-61)

Taylor happened across the body of a dead warrior who had been scalped by a soldier. He described the fallen foe – a finely built man, about thirty years old, who “looked like a bronze statue that had been thrown to the ground.” “I could not help a feeling of sorrow as I stood gazing upon him. He was within a few hundred rods of his home and family which we had attempted to destroy and he had died to defend.” Taylor brought away the man’s medicine bundle as “a souvenir of a very brave man in a memorable battle.”

Taylor says he later learned that the dead man was named High Elk, whose experiences during the battle we will never know. (76/63)

“No earthly chance.”

He turned next to outlining what he believed happened to Custer. (Among those who had ridden with Custer was Mark Kellogg, a reporter. Dr. G.E. Lord was the regimental surgeon.)

Captain Benteen would

later explain why he made no effort to go to Custer. He said, “there were 900

veteran Indians right there at that time, against which the large element of

recruits in my battalion would stand no earthly chance as mounted men.” He did

go straight for Reno, since he felt a fight was progressing and it “savored too

much of coffee-cooling” not to advance. (76/69)

(The

expression “coffee cooler” was applied to soldiers in the Civil War and after,

who sat around campfires, talking a good fight, blowing on their coffee until

it was the right temperature to drink, but who dawdled once shooting began, or never

joined the battle at all.)

____________________

“Among

the men it was felt then that their comrades had been needlessly sacrificed and

their own lives put in jeopardy to further ambition.”

____________________

Taylor and his comrades had been

trapped for two and one half days, and “it looked as if we had reached the end

of our earthly journey.” Finally, the forces of Gen. Terry and Gen. John Gibbon

arrived; and they were saved. A few short miles away, the bodies of Custer and

the men who rode with him were discovered. They had been stripped of all their clothing

and gear and looked, Taylor said, “like little mounds of snow.” The body of

Sgt. Butler was found. Several shell casings littering the ground, “evidence

that he had made a gallant fight.” The smell of death was sickening; but Taylor

saw soldiers sitting down close to mangled remains and “munching their bit of

hardtack and bacon.” Taylor pulled two arrows from one body and carried them

away. (These were be sold at auction in 1995.) Lt. William Cooke’s body could

be identified by his long black side whiskers, “one of which had been taken off

for a scalp, for if my recollection is correct the Lieutenant was a little

bald.” Among the men, Taylor says, there was “a deep feeling of resentment

against the General [Custer].” “Among the men it was felt then that their

comrades had been needlessly sacrificed and their own lives put in jeopardy to

further ambition.”

The Indians, too, had fled in haste.

On every hand as we rode along was

the evidence of a hasty flight, an immense number of lodge poles, robes,

dressed skins, pots, kettles, cups, pans, axes and many other articles among

which I saw several decorated box-like receptacles made of rawhide, a kind of

traveling trunk I suppose. Also sleeping mats, made of small willow sticks that

rolled up like a porch shade. Several war clubs were picked up with the

sickening evidence on them of a recent use.

Taylor says several soldiers hidden

in the woods had seen squaws mutilate the fallen soldiers from Reno’s attack. (76/73-78)

Separately, James McLaughlin, in a

book, My Friend the Indian, talked to

warriors who took part in the fight, having lived among the natives as an agent

for 38 years. They told him what happened when Custer and the men with him reached

the Little Big Horn River and tried to cross from a different direction. “As

the men [of Custer’s detachment] rode down into the bottom, the Indians saw

that they were apprehensive, but they did not falter and were well down to the

river before the Sioux showed themselves on that shore.” Gall, Crow King, Bear

Cap, No Neck and Kill Eagle could all see “the entire field covered by Custer’s

force.” The Cheyenne were led by Crazy Horse. Lame Deer, Hump and Big Road, and

they unleashed “a red tide of death.” So many warriors stormed across the ford

“they made the water foam.” Riders let out “wild yelps which they had learned

from the wolves.”

At least one soldier, well mounted,

seemed likely to escape, McLaughlin was told. He was drawing away from five or

six pursuers, but turned to look over his shoulder, “fancied himself nearly

overtaken” and killed himself with a shot to the head. Gall told McLaughlin that

“he would have gone at once to the attack of Reno when the fight on Custer Hill

was over, if he could have controlled his warriors.” “Some scores of horses

that had lately been ridden by the white man, the most valuable booty for an

Indian, were galloping about the country.” Other animals had been badly

wounded. After the fight, “Horses lay kicking and struggling, or sat on their

haunches like dogs with blood flowing from their nostrils.” (76/85-91)

|

Custer, red scarf, at right, meets his end. Painting on the internet. |

John Gibbon was in command of six

companies of the Seventh Infantry and four troops of the Second Cavalry.

Gibbon’s men had marched 178 miles “through the very heart of the Indian

country and without seeing any signs of enemy. Yet the very next night the

Sioux crept up to the camp and stole the ponies of the Crow scouts.” On June 25

Gibbon’s and Terry’s combined forces moved out at 5:30 a.m. Terry and the

cavalry pushed ahead after the infantry stopped to go into camp.

It commenced to rain about nine

o’clock and was as dark as a pocket, so much so that the men had to travel single

file and were then scarcely able to see the second man in front of them. To add

to their troubles the Gatling guns got stuck into a mud hole and were lost for

some time but finally made their appearance. (76/95-97)

When Terry and Gibbon’s men first heard

that Custer was dead, they didn’t believe it, and “presently the voice of doubt

was raised and the very story sneered at by some of the staff officers.” But

the truth was soon clear. Lt. James H. Bradley and his Crow Scouts had counted

194 bodies, one of which, based on photographs he had seen of the General, he

took to be Custer. Riders were seen in blue in the distance – but these were

warriors dressed in the clothes of dead troopers. Bradley spoke of the warriors

who covered the native retreat and the “terrific gallantry with which they can

fight under such an incitement as the salvation of their all.” (76/99-100)

“All doubt that a serious disaster

had befallen General Custer’s command now vanished,” remembered one soldier, “and

the march was continued under the uncertainty as to whether we were going to

rescue the survivors or to battle with an enemy who had annihilated him.” The

advancing column found signs of a hasty Sioux and Cheyenne retreat. Buffalo

robes, dried meat, blankets and all kinds of camp utensils lay scattered about.

Tom Custer’s heart had been cut out and a heart with a lariat attached was

found in the abandoned camp on the Little Big Horn. (76/104-105)

News of disaster reached the Far West, a steamboat that worked on the Yellowstone River, late on the

morning of June 27. At that time, the vessel was moored at the mouth of the

Little Bighorn. The water “teemed with pike, salmon and catfish.” Several

officers and the captain of the vessel were “engaged in the general pastime of

fishing.”

Taylor quotes a story about Curley [a

Crow scout who later claimed to be the only survivor of Custer’s force], coming

aboard, giving way “to the most violent demonstrations of grief, groaning and

crying.” He spoke no English; none of the whites spoke Crow. He took pencil and

paper.

First a circle and then, outside of

it, another. Between the inner and outer circle he made numerous dots,

repeating as he did so, “Sioux! Sioux!” Then he filled the inner circle with

similar dots, which, from his words and actions they understood him to mean

were soldiers. Then by pantomime he made his observers realize that they were receiving

the first news of a great battle in which many soldiers had been surrounded,

slain and scalped by the Sioux. (76/107)

Taylor notes: “Captain Marsh [of the Far

West] had caused a portion of the deck to be thickly covered with grass,

and over it had spread a lot of tent flies [canvas sheets], making the whole

like an immense mattress and in a short time, the fifty-two stricken men [wounded

from the battle] were placed on board and with them Keogh’s horse, Comanche.” (76/116)

Taylor notes: “‘Rounding up the

hostile,’ or in other words seeking to deprive a strange and brave people of

their birthright and all they held dear, was not altogether a picnic.” (76/118)

Taylor says a petition was circulated

among the men, asking that Reno be given command. “By his bravery and skill he

had saved the rest of the regiment from Custer’s fate,” it read.

“It was a d----d humbug, but what’s

the odds?” said Sgt. McDermott, of this gambit to save Reno’s reputation.

“Terry and Crook took up the trails

and followed them here and there for several weeks but fruitlessly, so far as

the original plan of the campaign was concerned.” (76/119)

Taylor wrote in a poem of his own, “On the Rosebud,” including these lines:

And all who followed our Custer

Knew well that a stranger to fear,

He would strike, be the odds ere so

many

As soon as their camps did appear. (76/122)

W.H.H. Murray would later meet

Sitting Bull. “His word once given was a true bond…He was a born diplomat.”

Murray was dismissive of the “only good Indian” phrase. “We laugh at the saying

now, but the cheeks of our descendants will redden with shame when they read

the coarse brutality of our wit.”

Sitting Bull,

…was a valiant and brave leader, he

was feared by his foes and loved and admired by his people. All white men were

the enemies of the Indians, and Sitting Bull’s logic would permit no other

conclusion. He believed that in transactions with them, the Indians would be

cheated and swindled. He wanted nothing to do with them, he had no land to sell

them at any time, and never gave an emissary of the Government the least

encouragement. (76/129-130)

Little-Big-Man was involved in the

death of Crazy Horse, in 1877, the former being a warrior one white called “one

of the greatest rascals unhung.”

Lt. John G. Bourke (On the Border with Crook) says of Crazy

Horse: “He had made hundreds of friends by his charity toward the poor, as it

was a point of honor with him never to keep anything for himself, excepting

weapons of war. I never heard an Indian mention his name save in terms of respect. (76/132)

Gall died in 1896, leaving one

daughter.

Rain-in-the-Face had been arrested

and confined to the guard house at Fort Lincoln. He escaped in April 1875 and

was said to have carried a grudge against Tom Custer. He spotted Tom during the

fight, said Custer’s brother recognized him, and when he got near enough “he

shot him…cut his heart… bit a piece out of it and spit it in his face.” This

was a story he told in 1894. Rain-in-the-Face, twice wounded, rode off with Tom

Custer’s heart in his hand. He died in 1905, age 62.

Revenge

of Rain-in-the-Face by

Longfellow

In that desolate land and lone,

Where the Big Horn and Yellowstone

Roar down their mountain path,

By their fires the Sioux Chiefs

Muttered their woes and griefs

And the menace of their wrath.

“Revenge!” cried Rain-in-the-Face,

“Revenge upon all the race

Of the White Chief with yellow hair!”

And the mountains dark and high

From their crags re-echoed the cry

Of his anger and despair.

In the meadow, spreading wide

By woodland and river-side

The Indian village stood;

All was silent as a dream,

Save the rushing of the stream

And the blue-jay in the wood.

In his war paint and his beads,

Like a bison among the reeds,

In ambush the Sitting Bull

Lay with three thousand braves

Crouched in the clefts and caves,

Savage, unmerciful!

Into the fatal snare

The White Chief with yellow hair

And his three hundred men

Dashed headlong, sword in hand;

But of that gallant band

Not one returned again.

The sudden darkness of death

Overwhelmed them like the breath

And smoke of a furnace fire:

By the river’s bank, and between

The rocks of the ravine,

They lay in their bloody attire.

But the foemen fled in the night,

And Rain-in-the-Face, in his flight,

Uplifted high in air

As a ghastly trophy, bore

The brave heart, that beat no more,

Of the White Chief with yellow hair.

Whose was the right and the wrong?

Sing it, O funeral song,

With a voice that is full of tears,

And say that our broken faith

Wrought all this ruin and scathe,

In the Year of a Hundred Years.

Certainly, Taylor seems to believe Reno had

been drinking before the fight. He cites a story written in 1904. Reno

supposedly told Reverend Dr. Arthur Edwards, “that his strange actions at the

battle of the Little Bighorn, were due to the fact that he was drunk.” Still,

he does not fault Reno for his retreat. What Custer “could not do with five

Companies, it is hard to believe that Reno could do with three.” The editor

notes that natives spoke often of recovering canteens from the field that

“contained copious amounts of liquor.”

“If he had only

added discretion to his valor he would have been a perfect soldier.”

Taylor writes: “I feel that overconfidence in himself [Custer], his officers and regiment, together with his underestimating the number of Indians until it was too late to change his plan of battle, were the two principle causes of his defeat.”

Taylor quotes one of Custer’s own officers, Cyrus T. Brady, a friend of the commander: “He was a born soldier, and specifically a born Cavalryman.”

If he

had only added discretion to his valor he would have been a perfect soldier…He

was impatient of control, and liked to act independently of others and to take

all the risk and glory to himself: …. A man of great energy and remarkable

endurance, he could out ride almost any man in his regiment, and was sometimes

too severe in forcing marches, but he never seemed to get tired himself, and he

never expected his men to be so.

Brady added: “Custer was more dependent than

most on the kind approval of his fellows, he was vain and ambitious, and fond

of display; but he had none of those great vices which are so common in the

army. He never touched liquor in any form and did not smoke, chew or gamble.” (76/142-144)

Taylor wrote again in a poem:

They all come back, those anxious hours,

Spent

on the barren hill

The

scattered dead with staring eyes,

Are

in my memory still. (76/145)

Two soldiers were the last to die from wounds, David

Cooney, on July 21, Frank Braun on October 4.

The Little Bighorn rises in the Bighorn Mountains.

Sheridan described it in 1877: “the water of this little river is the clearest

and coldest of any that we had met.” There were large cottonwood trees, box

elder, and ash. Roses and dogwood added their perfume. Mulberries, cherries and

black currants grew in the area “and it was easy to see why it was considered

by the Indians a most desirable summer camp.” Grass was so high, that Sheridan

said a rider could almost tie the tops from each side over a horse’s back. The

buffalo and Indian were all gone by the time he visited. In their place were

“prospectors, immigrants and tramps.” (76/151-152)

Three brave soldiers, traveling only by night,

laying low in day, took messages to Gen. Crook, to tell him of Custer’s defeat.

Taylor describes the appearance of the regular

fighting man, including his own:

A pair of pants that had once been blue, and

made of as good a grade of shoddy as the patriotic contractor could afford, had

become, through the hard usage given them by months of active service and

several patches made from a grain-bag, rather dilapidated as well as dirty,

used as they were to sleep in as well as ride in.

He topped it off with a black hat; but “the

rain and wind gave it an appearance unlike anything I ever saw on the head of a

man.” The brim was half off and so, said the soldier,

I was sometimes looking over the brim and

sometimes, under it. A cheap, coarse, outing shirt, the color of a dusty road,

and shy of buttons, was garnished by a large handkerchief that had once been

white, the sleeves of the shirt rolled up to the elbow. The blouse, a thin dark

garment, was strapped to the pommel of the saddle for the day was quite warm.

Taylor continued:

Around the waist a canvas belt full of

cartridges, below it another belt carrying a Colt’s revolver, while from

another broad leather belt passing over the left shoulder swung a Springfield

carbine. Rolled up and strapped to the saddle, was carried a blanket, piece of

shelter tent and an overcoat, while in various other places on the saddle were

hobbles, lariat, canteen and haversack. The saddle pockets contained an extra

horseshoe, nails, cartridges, currycomb and brush and sometimes a towel and

piece of soap, as well as any little extras a soldier might fancy. (76/155-156)

After the fight, the Indians picked up letters

written and never mailed from Custer’s men. A paymaster’s check made out to

Captain Yates, for $127.00, turned up in Indian hands at Fort Peck in November.

Mrs. Calhoun was later returned her husband’s watch. A heavy gold ring with a

bloodstone seal was recovered and sent to the mother of Lt. Van Reilly of the Seventh.

Crook was clear in assessing blame for the

troubles between the races: “Greed and avarice on the part of the Whites in

other words, the Almighty Dollar, is at the bottom of nine tenths of all our

Indian troubles.”

Lt. Colonel Richard I. Dodge: “Next to the

crime of slavery the foulest blot on the escutcheon of the Government of the

United States is the treatment of the so called wards of the Nation.”

General Miles on the capture of Joseph [and the

Nez Perce]: “they have been friends of the white race from the time their

country was first explored -- they have been, in my opinion, grossly wronged in

years past.” (76/159)

George Herendeen also gave an account of the

battle. He was born in Ohio in 1845 and came to Montana shortly after the end

of the Civil War. He described the scene on the morning of June 25, as Custer’s

scouts looked down from a high ridge:

From this point we could see into the Little

Horn Valley, and observed heavy clouds of dust rising about five miles distant.

Many thought the Indians were moving away, and I think General Custer thought

so, for he sent word to Colonel Reno, who was ahead with three companies of the

Seventh regiment, to push on the scouts rapidly and head for the dust.

Reno’s advance was quickly halted, of course. Soon the soldiers were driven back, and retreat “became a dead run for the ford. The Sioux, mounted on their swift ponies, dashed up by the side of the soldiers and fired at them, killing both men and horses. Little resistance was offered, and it was a complete rout to the ford.” Herendeen lost his own horse when it stumbled and fell. He saw several soldiers who were dismounted and some on horseback who had been left behind. “I called on them to come into the timber and we would stand off the Indians. Three of the soldiers were wounded, and two of them so badly they could not use their arms.” Later, he saw men on the bluff using butcher knives to dig rifle pits. Several times warriors charged cavalry lines, throwing stones.

I think in desperate fighting Benteen is one of

the bravest men I ever saw in a fight. All the time he was going about through

the bullets, encouraging the soldiers to stand up to their work and not let the

Indians whip them; he went among the horses and pack mules and drove out the

men who were skulking there, compelling them to go into the line and to do their

duty.

Many men had not had water for 36 hours, “some

had their tongues swollen and others could hardly speak. The men tried to eat

hardtack, but could not raise enough saliva to moisten them…” One man sent out

for water was killed, six or seven wounded “in this desperate attempt.” “We

expected the Indians would renew the attack the next day, but in the morning

not an Indian was to be seen.” “If Custer had struck the Little Horn one day

later or deferred his attack twenty-four hours later, Terry could have

cooperated with him, and, in all probability, have prevented the disaster.” (76/164-170)

Indians at Carlisle Indian School in in

Pennsylvania later shared their thoughts; one recalled that “the women with crying

babies on their backs left their teepees and retreated in a very disorderly

manner toward a large hill about two miles distant.” The soldiers [of Reno]

panicked, one said.

Men rode over each other and being frightened

themselves and their horses also, the retreat was made in a very confused

unmilitary order. Men running on foot and horses galloping madly, with the

Indians in their rear and on their flanks was the scene caused by the blunder

of a single man…

“I was 23 years old then,” said another Indian,

“so I was not afraid to face anything.” (76/171-172, 176)

J. F. Finerty described Cheyenne scouts, riding

with Gen. Nelson Miles in 1879, as men who “fight like lions…[yet] strange as

it may seem to my readers, are of gentlemanly deportment.” (76/180)

Roman Rutten, M Troop, saw Isaiah Dorman, his

horse killed, firing into the Indians. “As I went by him he shouted, ‘goodbye

Rutten.’” (76/182)

Sgt. John Ryan remembered M Troop losing its guidon

while crossing the river. One warrior later told a writer the Custer fight “lasted as long as it would

take a hungry Indian to eat his dinner.”

James McLaughlin later wrote of the skilled,

“generalship of Gall that kept the strength of the Indians concealed from the

white soldiers…” (76/186-187)

The officers of the Seventh Cavalry came to

their fates by many paths. First Lt. William W. Cooke was from Hamilton,

Canada; First Lt. Camillus “Charles” De Rudio was born in Italy. During the

Civil War he was an officer in the Second U.S. Colored Infantry. Captain Thomas

B. Weir was born in Ohio. He died while on recruiting duty in New York City,

December 9, 1876. Lt. Algernon E. Smith, F Troop, had been promoted for bravery

at Fort Fisher [during the Civil War]. KIA on June 25. Lt. Donald McIntosh was

a full blooded Indian, born in Canada. His G Troop, like F, was wiped out.

Second Lt. George D. Wallace was killed at Wounded Knee in 1890. Benteen also

led colored troops during the Civil War. Myles W. Keogh of I Troop was born in Ireland.

Lt. James Calhoun was also born in Ohio; he and his L Troop were wiped out.

Second Lt. John F. Crittenden was assigned to the infantry, but requested

transfer to the cavalry. He was born in Kentucky, a son of General T. L.

Crittenden. His father later requested that his remains be left where he fell.

Lt. Edward Gustave Mathey was born in France and served four years during the

Civil War. Dr. J. M. DeWolf was killed on Reno Hill.

*

I have some random notes on Custer

(check for sources later); may be Son of

the Morning Star; mutilation, p. 3, 6, 13, 131-132 by Native Americans vs.

U.S. p. 176

Benteen

said treat Indians fairly and there would be no problems; he was offended by

larceny of agents for the Indian Bureau.

Captain

Myles Moylan was “blubbering like a whipped urchin” after the defeat.

As a boy, Custer

once punched through a window to strike at a classmate making faces at him.

How many

warriors did the Seventh Cavalry run into: “You take a stick and stir up a big

ant hill; stir it up good and get the ants excited and mad. Then try to count

‘em,” said one soldier later.

Reno’s

men were so dry their tongues started to swell.

Custer

had four Crow scouts who left the column when Custer gave them permission; they

sensed disaster.

One

white officer/newsman (check) said of Indians: “They must be hunted like

wolves.” p. 132; 148-149

Sitting

Bull on Custer: “He was a fool and rode to his death.”

Untrained

soldiers were “the sport of Indians,” rolled off horses “like pumpkins.” (May

be a quote from Thomas Hart Benton.

Custer

had been fearless in leading charges during the Civil War, often rashly, at

Gettysburg. Even his attack at Washita in 1868 was badly scouted and a portion

of his command became separated and the Indians wiped it out. He had finished

last in his class at West Point.

Custer

notes: he has 40 Indian scouts; as the Seventh Cavalry departs more than two

dozen wives wave goodbye; the troops are leaving their sabers behind; each man has

100 rounds for a single-shot 1873 Springfield carbine, 24 for a revolver. (Many

Indians had 16-shot repeating rifles.)

Sitting

Bull is 42. Captain Edward S. Godfrey will later claim he took no part in the

battle, calling him “a great coward.” (Not exactly an unbiased account.)

“They

made such short work of killing them that no man could give any correct account

of it.” (a reporter relating what Hump had said)

“Had the

soldiers not divided, I think they would have killed many Sioux,” Red Horse

said after the fight.

Benteen had 115

Reno had 140 (had 40 killed, 13

wounded, many missing)

Custer had 210

These

numbers also vary from one source to the next.

One

estimate puts the Native American casualties at 100 dead, 150 wounded (I have

seen far lower).

|

Fancy moccasins for important occasions. |

|

Both images above from the blogger's collection. |

*

July 4: Trouble erupts in the town of Hamburg, S.C., then a haven for African Americans, and protected by its own militia.

Smithsonian notes:

On July 4 of that year, 16 months after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, white travelers provoked a confrontation by attempting to drive a carriage through the African American militia’s Independence Day parade on Main Street. After trying to force the militia to disband and surrender its weapons in court, one of the white travelers returned on the day of the hearing with more than 200 men and a cannon. The vigilantes [known by the nickname of “Red Shirts”] surrounded the militia in a warehouse, shot men as they tried to escape, captured the rest and tortured and executed six. Not one person was ever prosecuted for the murders.

In Congress, Joseph Rainey said the assassination of Hamburg leaders was a “cold-blooded atrocity.” He implored his fellow members, “In the name of my race and my people, in the name of humanity, in the name of God, I ask you whether we are to be American citizens with all the rights and immunities of citizens or whether we are to be vassals and slaves again? I ask you to tell us whether these things are to go on.”

“Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, elected governor of South Carolina in 1890 would later brag about the attack.

Again, Smithsonian tells the story.

“The leading white men of Edgefield” had wanted to “seize the first opportunity that the Negro might offer them to provoke a riot and teach the Negroes a lesson.” He added, “As white men we are not sorry for it, and we do not propose to apologize for anything we have done in connection with it. We took the government away from them in 1876. We did take it.”

Federal protection for African Americans in the South would soon be ended, as part of the deal to place Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House, after a contested election.

Hayes, too, would eventually speak ill of the effort to enfranchise the former enslaved peoples. To an all-white audience, he explained in 1890,

One of the devoted friends of the colored people tells us that “their ignorance, indifference, indolence, shiftlessness, superstition and low tone of morality are prodigious hindrances to the development of the great low country where they swarm.” It is, perhaps, safe to conclude that half of the colored population of the South still lack the thrift, the education, the morality, and the religion required to make a prosperous and intelligent citizenship [emphasis added].

The historian William Archibald Dunning and his graduate students would support this kind of argument when they worked to write state-by-state histories of the South during Reconstruction. Dunning’s prejudices were also clear. African American politicians of that era, he said, were “very frequently of a type which acquired and practiced the tricks and knavery rather than the useful art of politics, and the vicious courses of these negroes strongly confirmed the prejudices of the whites.”

John Schreiner Reynolds, influenced by Dunning, would write his own history, in defense of the white takeover in South Carolina. He described one African American politician as “a vicious and mouthy negro” who “lost no opportunity to inflame the negros against the whites.” As Reynolds told it, the Red Shirt violence at Hamburg was “the culmination of troubles which had long been brewing in and around the negro-ridden town.”

“Negro-ridden,” says it all.

*

July 4 (second entry): Nate Love, born into

slavery in Tennessee in 1854, goes on to become a cowboy in Texas. In Deadwood,

now South Dakota, he enters his first rodeo. Love takes first place in six

events, “kicking off a 15-year career that made him a legend across the

country.” (Smithsonian magazine, July/August 2022, p. 10)

*

The presidential election of 1876

proved to be one of the closest in U.S. history. The disputed results, and the

argument that followed, sounds somewhat like the disputed claims put forward by

Republicans in 2020.

____________________

“The

Democrats raised the cry of fraud. Suppressed excitement pervaded the country.

Threats were even muttered that Hayes would never be inaugurated.”

____________________

That year, the Democrats chose Samuel

J. Tilden of New York as their candidate for president, Thomas A. Hendricks of

Indiana for vice president. The Republicans ran Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio for

president, with William A. Wheeler of New York in the vice presidential slot.

Andrews writes:

The election passed off quietly,

troops being stationed at the poles in turbulent quarters. Mr. Tilden carried

New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut. With a solid South, he had won

the day. But the returning boards of Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina,

throwing out the votes of several democratic districts on the ground of fraud

or intimidation, decided that those states had gone republican, giving Hayes a

majority of one in the electoral college. The Democrats raised the cry of

fraud. Suppressed excitement pervaded the country. Threats were even muttered

that Hayes would never be inaugurated. President Grant quietly strengthened the

military force in and about Washington. The country looked to Congress for a

peaceful solution of the problem and not in vain.

The Constitution provides that the President

of the Senate shall, in presence of the Senate and House of Representatives,

open all the [electoral] certificates, and the votes shall be counted. Certain

Republicans held that the power to count the votes lay with the President of

the Senate, the House and Senate being mere spectators. The Democrats naturally

objected to this construction, since Mr. Ferry, the republican president of the

Senate, could then count the votes of the disputed states for Hayes.

The Democrats insisted that Congress

should continue the practice followed since 1865, which was that no vote

objected to should be counted except by the concurrence of both houses. The House

was strongly democratic; by throwing out the vote of one single state it could elect

Tilden.

The deadlock could be broken only by

a compromise. A joint committee reported the famous Electoral Commission Bill,

which passed House and Senate by large majorities; 186 Democrats voting for the

bill and 18 against it, while the republican vote stood 52 for and 75 against.

The bill created a Commission of five senators, five representatives, and five

justices of the United States Supreme Court, the fifth justice being chosen by

the four appointed in the bill. Previous to this choice the commission contains

seven Democrats and seven Republicans. It was expected that the fifth justice

would be Hon. David Davis, of Illinois, a neutral with democratic leanings; but

his unexpected election as a democratic senator from his State caused Justice

Bradley to be selected to the post of decisive umpire. The votes of all

disputed States were to be submitted to the commission for decision. (See: Year

1877, for resolution.)

*

The presidential election is not the only one to be disputed. Wade Hampton III is put up as a candidate for governor of South Carolina. He faces off against Republican incumbent, Daniel Henry Chamberlain.

Andrews explains:

The whites rallied to Hampton with

delirious enthusiasm. “South Carolina for South Carolinians!” was their cry. White

rifle clubs were organized in many localities, but the Governor disbanded them

as unsafe and called in United States troops to preserve order. In the white

counties the negroes were cowed, but elsewhere they displayed fanatical

activity. If the white could shoot, the black could set fire to property. Thus

crime and race hostility increased once more to an appalling extent. The

Hamburg massacre, where helpless negro prisoners were murdered was offset by

the Charleston riot, where black savages shot or beat every white man who

appeared on the streets. (11/225)

Initially, Chamberlain is declared the victor,

but a second count of ignored ballots from Laurens and Edgefield counties,

changes the count, and Hampton is elected instead. Both men claimed to be the

rightful governor, but Chamberlain eventually left the state the following

year.

No comments:

Post a Comment