____________________

“Let it be your sacred duty to make home happy for your children.”

Godey’s

Lady’s Book, advice for women

____________________

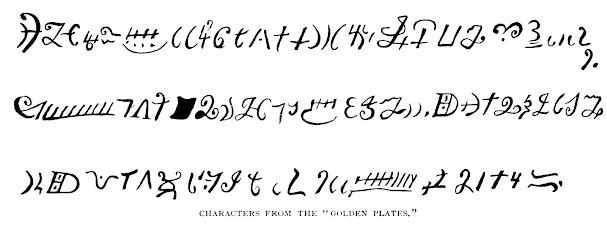

|

From the Book of Mormon. |

GODEY’S LADY’S BOOK announces

a campaign for “The Rights of Children,” and takes a stand against corporal

punishment. “Nothing can be more absurd in theory and vile in practice than the

attempt in common parlance ‘to break the temper’ and ‘to crush the will’…,

while of all debasing, degrading influences the worst is bodily fear.”

Seven years later, Hale printed a report by Lewis Gaylord Clark, describing schoolroom conditions. In one case, Clark wrote, “His [the schoolmaster’s] floggings were almost incessant.” One boy had his fingers feruled on the nails, “a refinement of cruelty which caused the little fellow’s nails to turn black and soon come off.” Hale argued that women should be placed in charge of primary schools, if for no other reason than that their “native feminine patience and understanding of children” would naturally incline them not to beat on their pupils.

A teacher today might appreciate her idea of what kind of job was involved. An educator should have “the patience of Job, the wisdom of Solomon, the ‘loving spirit’ of the beloved disciple, and the energy of Paul.”

Hale also wrote, “fathers and mothers, I beseech you, let it be your sacred duty to make home happy for your children.”

She added, “There is no influence so powerful as that of the

mother, but next in rank and efficacy is that of schoolmaster.” (113/230-231)

*

UNFORTUNATELY, no matter what some wives and mothers did, it was

not enough to establish a happy home, no matter what it might look like from

the outside. As Emerson wrote in 1844, “Every roof is agreeable to the eye, until it is

lifted; then we find tragedy and moaning women, and hard-eyed husbands.”

*

February 7: Joseph Smith, the founder and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints announces his plan to run for President of the United States. He outlines his platform.

Excerpts from the Joseph Smith Papers include:

No honest man can doubt for a moment, but the glory of American liberty, is on the wane; and, that calamity and confusion will sooner or later, destroy the peace of the people. Speculators will urge a national bank as a savior of credit and comfort. A hireling puseudo [sic] priesthood will plausibly push abolition doctrines and doings, and “human rights,” into Congress and into every otner [other] place, where conquest smells of fame, or opposition swells to popularity. Democracy, Whiggery and Cliquery, will attract their elements and foment divisions among the people, to accomplish fancied schemes and accumulate power, while poverty driven to despair, like hunger forcing its way through a wall, will break through the statutes of men, to save life, and mend the breach in prison glooms.

A still higher grade, of what the “nobility of nations” call “great men,” will dally with all rights in order to smuggle a fortune at “one fell swoop:” mortgage Texas, possess Oregon, and claim all the unsettled regions of the world for hunting and trapping: and should a humble honest man, red, black, or white, exhibit a better title, these gentry have only to clothe the judge with richer ermine, and spangle the lawyer’s fingers with finer rings, to have the judgment of his peers, and the honor of his lords, as a pattern of honesty, virtue and humanity, while the motto hangs on his nation’s escutcheon: “Every man has his price!”

Now, oh! people! people! turn unto the Lord and live; and reform this nation. Frustrate the designs of wicked men. Reduce Congress at least one half. Two Senators from a state and two members to a million of population, will do more business than the army that now occupy the halls of the National Legislature.

Petition your state legislatures to pardon every convict in their several penitentiaries: blessing them as they go, and saying to them in the name of the Lord, go thy way and sin no more. …

Let the penitentiaries be turned into seminaries of learning, where intelligence, like the angels of heaven, would banish such fragments of barbarism: Imprisonment for debt is a meaner practice than the savage tolerates with all his ferocity. “Amor vincit omnia.” Love conquers all.

Petition also, ye goodly inhabitants of the slave states, your legislators to abolish slavery by the year 1850, or now, and save the abolitionist from reproach and ruin, infamy and shame.

Make HONOR the standard with all men: be sure that good is rendered for evil in all cases: and the whole nation , like a kingdom of kings and priests, will rise up with righteousness: and be respected as wise and worthy on earth: and as just and holy for heaven, by Jehovah the author of perfection.

Oh! then, create confidence! restore freedom! break down slavery! banish imprisonment for debt, and be in love, fellowship and peace with all the world! Remember that honesty is not subject to law: the law was made for transgressors: wherefore a Dutchman might exclaim: Ein ehrlicher name ist besser als Reichthum, (a good name is better than riches.)

As to the contiguous territories to the United States, wisdom would direct no tangling alliance: Oregon belongs to this government honorably, and when we have the red man’s consent, let the union spread from the east to the west sea; and if Texas petitions Congress to be adopted among the sons of liberty, give her the right hand of fellowship; and refuse not the same friendly grip to Canada and Mexico: and when the right arm of freemen is stretched out in the character of a navy, for the protection of rights, commerce and honor, let the iron eyes of power, watch from Maine to Mexico, and from California to Columbia; thus may union be strengthened, and foreign speculation prevented from opposing broadside to broadside.

Seventy years have done much for this goodly land; they have burst the chains of oppression and monarchy; and multiplied its inhabitants from two to twenty millions; with a proportionate share of knowledge: keen enough to circumnavigate the globe; draw the lightning from the clouds: and cope with all the crowned heads of the world.

The southern people are hospitable and noble: they will help to rid so free a country of every vestige of slavery, when ever they are assured of an equivalent for their property.

In the United States the people are the government; and their united voice is the only sovereign that should rule; the only power that should be obeyed; and the only gentlemen that should be honored; at home and abroad; on the land and on the sea: Wherefore, were I the president of the United States, by the voice of a virtuous people, I would honor the old paths of the venerated fathers of freedom: I would walk in the tracks of the illustrious patriots, who carried the ark of the government upon their shoulders with an eye single to the glory of the people: and when that people petitioned to abolish slavery in the slave states, I would use all honorable means to have their prayers granted: and give liberty to the captive; by paying the southern gentleman a reasonable equivalent for his property, that the whole nation might be free indeed!

…and when the people petitioned to possess the teritory [sic] of Oregon or any other contiguous teritory; I would lend the influence of a chief magistrate to grant so reasonable a request, that they might extend the mighty efforts [sic] and enterprize [sic] of a free preople [sic] from the east to the west sea; and make the wilderness blossom as the rose: and when a neighboring realm petitioned to join the union of the sons of liberty, my voice would be, come: yea come Texas: come Mexico; come Canada; and come all the world – let us be brethren: let us be one great family; and let there be universal peace. Abolish the cruel custom of prisons, (except certain cases,) penitentiaries, and court-martials for desertion; and let reason and friendship reign over the ruins of ignorance and barbarity; yea I would, as the universal friend of man, open the prisons; open the eyes; open the ears and open the hearts of all people, to behold and enjoy freedom, unadulterated freedom: and God, who once cleansed the violence of the earth with a flood; whose Son laid down his life for the salvation of all his father gave him out of the world; and who has promised that he will come and purify the world again with fire in the last days, should be supplicated by me for the good of all people.

With the highest esteem, I am a friend of virtue, and of the people,

Joseph Smith

Nauvoo, Illinois, February 7, 1844

*

JAMES WICKES TAYLOR reports again on the Millerites, noting,

March

23. The

“end of the world” is expected to day, according to Miller’s horoscope, but so

far (10 A.M.) every thing remains in statu quo – “no signs of wo, that

all is lost,” so far as I have observed... (102/57)

*

May 4: At the Tenth Anniversary of the American Anti-Slavery Society, held in the city of New York, and after “grave deliberation, and a long and earnest discussion,” delegates vote by nearly 3 to1,

that fidelity to the cause of human freedom, hatred of oppression, sympathy for those who are held in chains and slavery in this republic, and allegiance to God, require that the existing national compact should be instantly dissolved; that secession from the government is a religious and political duty; that the motto inscribed on the banner of Freedom should be, NO UNION WITH SLAVE-HOLDERS; that it is impracticable for tyrants and the enemies of tyranny to coalesce and legislate together for the preservation of human rights, or the promotion of the interests of Liberty[.]”

“We charge upon the present national compact,” they add, “that

it was formed at the expense of human liberty, by a profligate surrender of

principle, and to this hour is cemented with human blood.”

*

“A draft of a new community in his waistcoat pocket.”

June 27: The New Yorker has an excellent book review by Casey Cep, on Benjamin E. Park’s Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier. It was in 1844 that the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints, Joseph Smith, announced that he would run for President of the United States, in part because none of the major political parties would promise to protect his flock.

His “campaign” would be cut short on June 27, when a mob stormed

the Carthage, Illinois jail where he was being held, and murdered him.

|

Joseph Smith. (All photos in this post from author's collection.) |

I’ll quote Ms. Cep, for the most part. Park, she explains, traces Smith from his earliest forays into religion. He was only 21, in 1827, during the Second Great Awakening, when he dug up the golden tablets, from which the Book of Mormon comes. The angel Moroni, Smith claimed, had appeared to him several times before, finally telling him to go to the Hill Cumorah and dig for the plates. Smith had married Emma Hale by then, and she helped transcribe the words as her husband translated, from a language he called “reformed Egyptian.”

Cep writes:

Smith finished the transcription by

1830 and found a printer who agreed to run off five thousand copies. The

result, the Book of Mormon, begins as the record of a Jewish family in

Jerusalem, who, around 600 B.C., build a boat and sail to the Americas – where,

six centuries later, the risen Christ preaches to their descendants. In an age

when people were hungry for evidence of God’s continued involvement in the

world, and in a country anxious to assert itself on the global stage, Smith’s

scriptures offered appealing assurances: not only was the United States a holy

land where Jesus himself had walked but God was still speaking to the men and

women who lived there.

At first, Smith gathered a small circle of followers, usually men and women of modest means. His claims to have discovered the new word of Christ did not sit well with many of his neighbors. Mormons occasionally spoke in tongues, and they insisted that “other churches had fallen away from Christ’s true gospel.”

On one occasion Smith was arrested as a “disorderly person.” Mormons suffered more. “Anti-Mormon mobs harassed known believers and attacked their houses; they even tarred and feathered Smith one night in 1832.”

Cep notes the Mormon’s movements, west to Kirtland, Ohio, then, amid allegations of banking fraud, west again to Independence, Missouri, and west a third time, to Far West, Missouri.

A growing Mormon population began to assert its voting power. Serious bloodshed soon resulted:

In 1838, having already been evicted

from one Missouri county, they went to vote in the county seat of another,

where a mob attempted to stop them. There were allegations of violence in what

came to be known as the Gallatin County Election Day Battle, and subsequent

vigilantism left more than twenty people dead. During this period, the Missouri

governor, Lilburn Boggs, declared in an executive order that “the Mormons must

be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if

necessary for the public peace.” Three days later, seventeen Mormons were

murdered by soldiers near Shoal Creek, in Caldwell County.

Cep notes that the next day, Smith was arrested. He spent four months in prison. Thousands of Mormons retreated to Illinois, where they were promised some protection by the governor. Smith himself escaped and fled Missouri. He and other church leaders headed for Washington D.C. with hundreds of petitions asking compensation for lost property and damages. Smith asked for $100,000. “What can I do?” President Van Buren responded. “I can do nothing for you.”

Mormon leaders returned to Illinois, bought the town of Commerce, and renamed it Nauvoo, which Smith believed was Hebrew for “beautiful city.” Cep does an excellent job of summarizing Park’s book and highlighting key Mormon ideas. “The city of Nauvoo,” she writes, “took shape in an age when Ralph Waldo Emerson claimed that every intellectual had ‘a draft of a new community in his waistcoat pocket.’”

Smith was doing more than building castles in the sky. His flock grew to 20,000. Nauvoo was “more populous than Chicago.”

Cep also notes that when Gov. Boggs was shot, in 1842, “rumors circulated that Smith had placed a bounty on his head. Missouri forced Illinois into an extradition arrangement for the Mormon leader, but the municipal courts in Nauvoo thwarted it, in a scandalous act of disregard for the rule of law.”

Unlike the Windy City, Cep explains,

Nauvoo, operating under a permissive

charter from the state of Illinois, developed a distinctly theocratic

character: its independent judiciary could deny the validity of arrest warrants

issued by neighboring authorities in order to shield Church members from

prosecution, and its standing militia of several hundred armed men, known as

the Nauvoo Legion, was empowered to protect citizens from any threat. Smith was

made a Lieutenant General, a title previously held in the United States only by

George Washington, and organized parades to show off the legion’s strength.

The Latter Day Saints also built an enormous tabernacle, twice as high as the White House; but serious troubles lay ahead.

The story of polygamy in the church is well known, but details are debated. Here, Cep can tell the story, as she says Park has related it:

Smith had continued to receive

revelations about how the faithful were meant to serve God, so this new

sanctuary housed new religious rituals. One of them called for posthumous

baptism, through which Mormons could baptize a living person as a proxy for

someone already deceased. Another – which would divide the Church, attract

the permanent suspicion of the state, and forever taint the public perception

of the faith – called for plural marriage.

The origins of this rite are not well

known. As Park observes in Kingdom of Nauvoo, it is striking that a

faith so devoted to record-keeping did not document the doctrine of polygamy.

“As committed as he was to the ritual’s significance,” Park writes, of Smith,

“he was similarly committed to its secrecy, knowing that its exposure would

lead to Nauvoo’s downfall.” Smith publicly denied knowledge of polygamous

marriages, and the few records of those unions which do exist refer to them as

“sealings” – or – even more cryptically –

simply connect the names of the united with “was,” an abbreviation for

“wed and sealed.” One of the only documents Smith ever recorded which attests

to the practice is a blessing he wrote for the family of one of his teen-age

wives, assuring her and her relatives of their salvation. Another of Smith’s

plural wives – whose marriage to Smith was followed, within a few weeks, by

that of her sister – later explained that these marriages were “too sacred to be

talked about.” Such furtiveness makes it difficult to track the development of

the doctrine, much less Smith’s theological justification for it. Some

historians, including Park, believe that he took his first plural wife in April

1841, though whenever it happened, he did not tell Emma, and it was some time

before she learned the truth.

By 1844, Park writes that Smith had taken more than thirty wives, the youngest age 14, the oldest age 56.

BLOGGER’S NOTE: I believe

this number would be disputed by current members of the Church of the Latter

Day Saints. I leave it to the readers to think for themselves.

Cep continues:

Originally, only Smith had multiple

wives. But he gradually revealed the practice to other Mormon leaders, inviting

them, selectively, to witness his plural marriages, then encouraging them to

pursue their own. Not everyone approved: Smith’s brother Hyrum initially led

the opposition, condemning polygamy and calling for a moral revival in Nauvoo.

Hyrum was a widower, and his hostility to the practice weakened after he

learned of its supposed posthumous benefits, through which he could be united

in the afterlife with both his late wife and any future ones. Other Mormons

remained unenthusiastic. Emma tried to marshal resistance among women through

the Church’s all-female Relief Society; in response, Smith tried to stifle the

organization. Emma then threatened him with divorce, at which point he promised

to take no additional wives and signed his property over to her and their

children, in order to secure their financial well-being in case of rival

claims.

If Parks is right, duplicity was involved. Cep writes:

It would be years before any Mormon

leader formally acknowledged the practice of polygamy. Instead, somewhat

shockingly, the Nauvoo city council passed a law punishing adultery with six

months in jail and a fine of up to a thousand dollars. (Because the city’s

municipal leadership overlapped entirely with its spiritual leadership, Smith

could choose to protect colleagues from prosecution under this new law.) Even

more audaciously, Smith cursed “all Adulterers & fornicators” in a speech,

then excommunicated two Church leaders for attempting to expose his secret

marriages. The first, John C. Bennett, had been the mayor of Nauvoo; when

his own polygamy became public, he accused Smith of having sanctioned it. The

second, William Law, had denounced plural marriage after Smith propositioned

his wife. After being banished from the faith, Law started a breakaway movement

called the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

A review in Time (1/23/17), of A House Full of Females, includes this line by a Mormon woman, after the birth of her son in the mid-1840s: “May he be the father of many lives/But not the Husband of many Wives.”

It would not be until 2016, that the minutes of the Council of Fifty, which governed Nauvoo, would be unsealed for historians to review. Smith first convened it in 1844, and members set to work “drafting an alternative to the United States Constitution.” Democracy was rejected as a “failed political project,” and was to be replaced, for Mormons, by a theocratic kingdom. The Council declared Joseph Smith to be “Prophet, Priest & King.”

.jpg) |

Joseph Smith and his followers built up a thriving city. |

.jpg) |

A member of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints leads a tour of Nauvoo. |

.jpg) |

The faithful cut stones for a great temple. (The photo is marred by light reflected on a glass case.) |

.jpg) |

The Temple at Nauvoo - cutaway view. |

|

The temple was burned in 1848, by an arsonist. For many years the site was a hole in the ground. |

.jpg) |

The Temple at Nauvoo, rebuilt in 2002. (Photo from 2025.) |

“The glory of American liberty is on the wane.”

As part of his presidential platform, Smith called for the annexation of Texas. He also suggested that money from the sale of public lands could be used to buy the freedom of enslaved persons.

According to Parks, Smith had sent letters to five other presidential candidates, only three of whom responded. None expressed any real interest in protecting the Mormons if they were elected.

Smith then declared his candidacy:

Persecution has rolled upon our heads

from time to time, from portions of the United States, like peals of thunder,

because of our religion. And no portion of the Government as yet has stepped

forward for our relief. And in view of these things, I feel it to be my right

and privilege to obtain what influence and power I can, lawfully, in the United

States, for the protection of injured innocence.

The Time review, mentioned above, included several examples of Smith’s political positions. “No honest man can doubt for a moment but the glory of American liberty is on the wane,” he warned, “and that calamity and confusion will sooner or later destroy the peace of the people.”

He called for prison reform: “Petition your state legislatures to pardon every convict in their several penitentiaries, blessing them as they go, and saying to them, in the name of the Lord, Go thy way, and sin no more. Imprisonment for debt is a meaner practice than the savage tolerates, with all his ferocity.”

He also called on followers to petition Congress to end slavery by 1850. “We have had Democratic presidents, Whig presidents, a pseudo-Democratic-Whig president and now it is time to have a president of the United States; and let the people of the whole Union, like the inflexible Romans, whenever they find a promise made by a candidate that is not practiced by an officer, hurl the miserable sycophant from his exaltation, as God did Nebuchadnezzar, to crop the grass of the field with a beast’s heart among the cattle.” “…I would honor the old paths of the venerated fathers of freedom.”

Not long after he declared for office, Smith was sent to jail (here we are back to Cep’s review as our source). Trouble developed when William Law and a group of dissenters began publishing a newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, accusing Smith of polygamy and calling him a threat to democracy.

The Council of Fifty ordered the Nauvoo Legion to destroy Law’s press; and Smith declared martial law.

Murder in Carthage.

The state of Illinois responded by

threatening military retaliation against Nauvoo, and by adding a new charge to

all the outstanding ones against Smith: attempting to incite a riot. Smith

surrendered himself at Carthage, the county seat. Two days later, a mob of more

than two hundred men stormed the jail where the Prophet was being held and shot

him as he tried to escape by jumping from a second-story window. He died not

long after hitting the ground, either from the fall or from the bullets the mob

fired at him once he landed.

Only five of the vigilantes were tried

for Smith’s murder, and none were convicted.

The later history of the church is better known. Sidney Rigdon, Smith’s First Counselor, tried to take control. Brigham Young, a member of an advisory council called the Quorum of Twelve, suggested instead that the Quorum take charge, with Young as president. Rigdon was later excommunicated, established a rival church, and condemned polygamy. Cep describes Young, a former carpenter:

Young was a forceful figure – “a man of

much courage and superb equipment,” per the weathered stone that marks his

birthplace, in Whitingham, Vermont. Ignoring the criticisms of the surrounding

secular authorities, he began to “marry for eternity” more than a dozen women,

seven of whom had also been “M.E.” to Smith, while also organizing the Mormon

vote for county elections. The state retaliated by revoking Nauvoo’s charter,

and the antagonism between the theocratic city and its surrounding democratic

neighbors intensified until, finally, the Mormons were forced out of Nauvoo.

There was some talk in this period about establishing a “sovereign reservation” where the Mormons could practice their faith in peace, like those granted to Native Americans. The battles between religion and law continued for another sixty years, at least. “In Reynolds v. United States (1879),” Cep explains, “the Justices ruled that the free-exercise clause did not protect plural marriage, and that a federal law banning polygamy was constitutional. Congress then passed more laws punishing the Church, including one that called for the seizure of its property.”

As is true with almost everything, the decision in Reynolds can be found online.

It was not until 1896 that Utah was admitted to the union as a state, after the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints agreed to give up polygamy. For the first time, then, a Mormon was elected to serve in Congress. Reed Smoot, a member of the Quorum of Twelve, was chosen for a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1903; but, as Cep notes, “he endured several years of congressional inquiries into whether his duties as a Mormon apostle would keep him from exercising secular authority.”

No comments:

Post a Comment