|

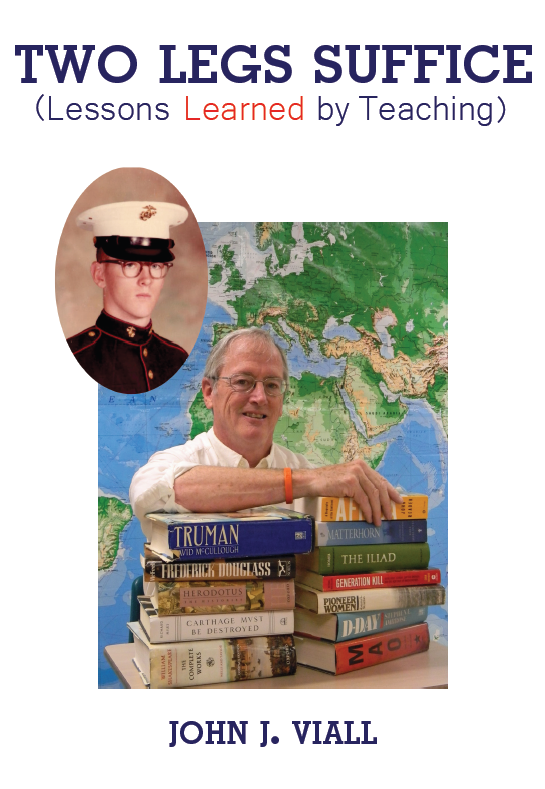

Jackpot in the ground. Some of the coins found in 2013. |

Discussing

the Gold Rush was always fun; and if nothing else, I always thought history was best when history was interesting. (That lesson often seems to have escaped the publishers of textbooks.)

In my class, I found students rarely knew what year gold was discovered in California, why the San Francisco 49ers of the NFL were named the “49ers,” or why their colors were red and…gold.

In my class, I found students rarely knew what year gold was discovered in California, why the San Francisco 49ers of the NFL were named the “49ers,” or why their colors were red and…gold.

Once we began our discussion, students often asked why the first discoverers didn’t keep their secret. I always told them “think like yourselves.” Who might you want to

tell? And would you want to brag or would you have trouble keeping a secret?

Most students also seemed unclear about what the term “prospector” meant. I

used to make fun of myself (I had one date during high school—and that was when

a friend’s sister asked me to a dance; I couldn’t dance worth a darn, either).

I would pick some young man, and put the idea to him: You are going to ask out

your dream girl. What are the “prospects” or chances she says yes.

We also talked about “prospects” in the NBA draft.

There are all kinds of good examples to use to stir student interest. One

story I used every year (and can’t find right now) involved a rush in

the Amazonian jungles of Brazil, touched off in 1985. The first “find”

was accidental, when loggers scouting for promising sites came upon an uprotted

forest giant. In the roots they found several gold nuggets. A mad

rush followed. In one case, miners uncovered a “nugget” the size

of a briefcase. I always reached behind my desk and thumped down my briefcase

to make a point.

I retired from teaching in 2008; but my memory is that the “nugget” was worth $1.4 million. I do remember that the miners broke it up, fearing it would end in a museum and they’d

be cheated somehow. But (see below), it would have had to weigh almost a

thousand pounds to be worth that much.

Gold,

of course, is much denser than almost any other element. A gold bar the size of

a brick would weigh fifty pounds. As of today, as I type this up

(11/8/18), gold is selling for $1,228 an ounce.

A

pound of gold (there are only 12 Troy ounces per pound) would then be worth

$14,736.

Other

terms and details I thought students should know: the terms vigilante, lynching

and stake a claim, pan out. (The term “stake a claim” comes from the habit of

miners driving markers at the four corners of their claims to indicate property

had already been taken.) The prejudice directed at non-white miners also seemed

important to discuss. The Chinese, for example, were not allowed to own land,

vote, serve on juries or testify against whites.

One

immigrant who “struck it rich,” was Levi Strauss, who left Bavaria in 1848 and

arrived in San Francisco in 1853. Strauss was soon selling heavy duty work pants

to miners, using rivets at points of strain to make them more durable. In 1873

he patented these pants, today known as jeans.

*

Finding

gold in 1849 was not unlike winning the lottery now. One couple that “struck it

rich” deserves special mention. In 2013 a

California couple walking

their dog noticed a can buried near a tree in their backyard. Inside, they found

1,427 gold coins, dating from 1847-1894. In May 2014 they began auctioning them

off, the first coin going for $15,000.

The

total estimated value: $11 million.

*

If you are not familiar with the

story of the S.S. Central America, my

students were always intrigued.

The book Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea chronicles the story in great and

often exciting detail.

Loaded with gold minted in San

Francisco, the vessel was sailing for New York in 1857 when caught in a violent

Atlantic storm. The Central America

soon went down, taking three tons (or perhaps fifteen

tons, sources differing) of gold and 425 passengers and crew with her. For the next 125 years no one gave

much thought to finding the wreckage. A man named Tommy G. Thompson, who had

studied engineering and robotics at Ohio State, began studying old records.

Eventually, he and a company he had founded with 160 other investors discovered

the wreck in 7,000 feet of water (some sources say 8,000).

A great deal of detective

work and searching of possible wreck sites were involved; one summer was

spent on a site of another vessel, sunk around the same time, which fit the

proper profile. Eventually robot cameras located the right wreck. Thompson and

others first looked at a series of pictures snapped by the robot. Thompson

described what they saw now:

“It was just…it was just…covered with gold!

I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it! That was the most thrilling….We

had hit right on a pile, nice low pictures, nice and clear. I mean everything

was perfect, man. It was incredible! But I looked at it, and I looked up, and,

Naaaah, this can’t be. I thought, That’s gotta be a bunch of brass laying

there. So I looked again! Holy! And I just started looking at the other shots,

and I…mean…it…was…PILES! I’m not kidding you, it is awesome! It is absolutely

awesome! Stacks of coins and bars of gold of every size and shape just sitting

there!” (Ship of Gold, p. 450)

Some of the coins were still in neat sacks, the bags they were

contained in having long since rotted away.

In another scene from the book a

robot camera is filming the ocean bottom. The submersible approached a beam

sticking up. Nearby, a hundred gold coins, washed by some current glinted in

the searchlight. Other hints of bars and coins showed under a layer of

sediment. An operator above pointed the forward thruster downward and shot out

a gentle wash of water to blow away the covering.

The

sediment was thin, but when the wake of the thruster hit, it exploded upward,

swirling into clouds, blotting out the rotted timbers, turning the monitors

white. For several minutes the techs could see nothing but the roiling

sediment. Then the clouds began to drift with the light current; the picture on

the monitorys began to clear and slowly revealed a scene few people could

imagine.

“The bottom was carpeted with gold,” Tommy

said. “Gold everywhere, like a garden. The more you looked, the more you saw gold

growing out of everything, embedded in all the wood and beams. It was amazing,

clear back in the far distance bars stacked on the bottom like brownies, bars

stacked like loaves of bread, bars that appear to have slid into the corner of

the room. Some of the bars formed a bridge, all gold bars spanning one area of

treasure over here and another over here, water underneath, and the decks

collapsed through on both sides.Then there was a beam with coins stacked on it,

just covered, couldn’t see the top of the beam it had so many coins on it.” (p.

452)

Author Gary Kinder describes what the recovery team saw that

day:

So many bricks lay tumbled upon one another

at myriad angles that the thrity-foot pile appeared to be the remnants of an

old building just demolished. Except these were bricks of gold: bricks flat,

bricks stacked, bricks upright, bricks cocked on top of other bricks. And coins

single, coins stacked, coins once in stacks now collapsed into spreading piles,

some coins mottled in the ferrous oxide orange and brown from the rusting

engines, others with their original mint luster. Besides a tiny squat lobster

carefully picking its way across piles of coins, the scene lay perfectly still.

One team member laughed, “Look at theose damn fire bricks.” A pink-orange

anemone drifted softly through the scene. “Stiking up out of another area was a

coin tower,” Kinder writes, “eight stacks of gold coins, twenty-five coins to a

stack, all of the stacks abutting one another like poker chips still in the

rack, the whole thing frozen together and angled upward at sixty degrees.” The

camera on the underwater vehicle could swivel; and now they saw “a mound of

gold dust frozen ten inches high, dotted with nuggets, and capped by two small

gold bars.” (p. 453)

The camera

swung again, briefly passing a coin standing straight up. Tommy had caught the

date. The camera was swung back.

Everyone laughed as Moore tapped the camera

back again. There stood a coin upright, face front, just as pure and lustrous

as the day it left the San Francisco Mint. It was emblazoned with the bust of

Lady Liberty, lovely in profile, her hair crossed with a tiara and cascading in

ringlets down her neck, thirteen stars surrounding her, and her ringlets

stopping just short of the date “1857.” In a pocket thirty feet across, the

ocean floor lay covered with these coins.

Doering [another member of the recovery

team] figured he had now seen more gold coins in one place at one time than any

other treasure hunter in history, and that included Cortes and Pizarro. He was

ready to pluck some of that gold from the ocean floor, drop it into the

artifact drawer, and bring it to the surface, so he could feel it right there

in the palm of his hand. 9p. 455)

New technologies had to be developed

to bring the coins up, unscratched, making them many times more valuable. (It

was soon decided to lower a long, wide hose down to the site, coat the coins in

silicon, pick them up and drop them in a drawer on the robot vehicle, the pull

them out at the surface, unmarred.) There were gold bars fifteen times larger

than anything then known to exist. The estimated value of the haul was $400

million; but there were multiple court challenges ahead—including one from an

insurance company that had paid off the losses back in 1857.

In the end, Thompson prevailed, and

the treasure was declared to be his; but he later ran off and left investors

with the same amount of gold they started with, which would be none. Thompson sold

his share of the gold, including 532 gold bars and a trove of coins, for

$50 million. A lengthy manhunt ended with his arrest in 2015; but when last I

checked he was still in jail and refused to reveal what had become of all the

treasure. At least some of it had probably gone into a trust fund for his

children.

|

Some of the gold from the wreck. |

|

Coins and bars thousands of feet below the surface. |

|

Gold bars cleaned up for display: each is worth tens of thousands (or more). |

*

The journals of

Alfred Doten, who left Plymouth, Massachusetts and sailed for California in

1849 also look promising as a source. I till check them out further soon.

*

My students

also liked the story of Bodie, California, a town founded in 1859 after another

gold find. William Bodey, who found the first gold, later died in a blizzard.

During its heyday, 1877-79, the town had a population of 11,000. The town

reportedly had a murder per day, on average; and it was said the teacher went

to school heavily armed.

Various

criminals came to no good end. Buffalo Bill Gross was stealing firewood; one

victim tired of his losses, cut out part of a log, filled it with gunpowder,

and sealed it up. Bill stole his firewood again and soon blew himself up. Two

other men were digging up new graves ans stealing the caskets. A stage was

robbed, and $30,000 in gold taken, but the robbers were caught, and the gold

never found. At least one criminal escaped from a flimsy jail, by pushing a

piano through the wall. As was often the case, prejudice against the Chinese

was rampant. They were buried separately from the whites. A fire swept the town

in 1892, doing significant damage and speeding the downhill slide.

The town, on

the border of Nevada and California is at 8,379 feet above sea level, sitting

in an almost treeless valley. Temperatures can drop to 30 or 40 degrees below

zero. There can be eight or ten feet of snow blanketing the town during the

winter. And when the gold ran out, the people soon began to trickle away. About

$95 million was taken from the mines (not sure of what point that figure was

computed). By the 1930s it was a ghost town, now a State of California

historical site.

|

Bodie, California: Present population: 0. |

|

My students liked writing ghost stories about Bodie. |

|

Pool table left behind when the last inhabitants left. |

|

Abandoned buildings, Bodie. |

*

Notes from the following story, Ralph K. Andrist in “Gold!” (American Heritage), may be of use to teachers. In the summer of 1847, John Sutter, a large land owner in California sent a carpenter, James Marshall, up the American River to build a sawmill. Months later, Marshall made his famous discovery:

January 24, 1848: Marshall lets the water run

all night, to clean debris from the millrace in preparation for putting the sawmill into operation; and on this morning he spots yellow specks in the

millrace. The men Sutther has hired continue to work, panning for gold only on

Sundays, until the mill is finished in March. The first nugget, found by

Marshall was about the size of a dime. The people of San Francisco, then a town

of about 900, did not much believe early reports of gold.

A group of Mormons began

digging about 25 miles from the sawmill, what became known as Mormon Diggings.

Sam Brannan, a store owner with a

place in Sutterville, near Sutter’s Fort, headed for San Francisco in May; with

him he brought a vial of gold dust; it is said he walked the streets shouting,

“Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” and waving his vial. This sparked

the first, local rush. Within two days boats were leaving San Francisco and headed for the

diggings. There they found Brannan’s store stocked with supplies and equipment

needed to go prospecting. By June it is estimated only 100 people remained in San Francisco. According to the alcalade, workers constructing a school house in Monterey,

California, heard the news, “threw down their saws and planes, shouldered their

picks, and are off for the Yuba. Three seamen ran off from the Warren,

forfeiting their four years’ pay; and a whole platoon of soldiers left their

colors behind.” The stories continued to get better and better; there were said

to be streams “paved with gold.” The mines, said one authority, exceeded “all

the dreams of romance and all the golden marvels of the wand of Midas.”

A miner later wrote his wife, “I do

not like to be apacking a thousand dollars about in my coat pockets for it has

toar my pockets and puld the Coat to pieces.”

On December 5, President Polk, in his

annual message, gave official blessing to the accounts. There were reports of

rich veins as “would scarcely command belief.”

Sutter ended up with “his cattle

butchered, his fields trampled and untended, his land taken by squatters, until

he had not a thing left.”

After Polk’s announcement, the rush

was on. The Argonauts, as they were called (after Jason and the golden fleece)

had two water routes; almost all available ships were taken over; the New

England whaling fleet was suddenly transporting passengers. As fast as vessels

reached SF, their crews deserted and headed for the gold fields, leaving the

harbor a forest of masts. Those going by the shorter route, across Panama, died

by the undreds from malaria, cholera and unsanitary conditions. Hiram Pierce, a

New York blacksmith, left a wife and seven children behind. He wrote home about

“swineish” behavior by the passengers and a ship’s doctor almost always drunk.

One night the doctor became tangled in his hammock and was hanging upside down

until morning. Another time, “the same worthy took a dose of medicine to a

patient & haveing a bone in his hand knowing, he took the medicine &

gave the bone to the patient.”

Others crossed by land in the spring.

Spring found one man ready to jump off for the trip West, armed with a rifle

and accompanied only by his bulldog. He was planning to walk to California—and

had already walked all the way from Maine. Another man planned to push a

wheelbarrow to the fields. Cholera, brought from Europe to New Orleans in 1848,

now spread up the river and was carried across the plains by the wagon trains.

In parts of Utah and Nevada the water and grass were bitter with sulpher,

alkalai and salt, even poisonous. One barren stretch had to be crossed in one

jump, usually lasting 24 hours; at Boiling Springs, halfway, water could be

poured into troughs and allowed to cool, and then proved drinkable, albeit

unappetizing. Animals, already worn from the trail, gave out during this

stretch, what one writer calls “the Forty-Mile Desert.” A traveler wrote, “The

forty-five mile stretch is now almost impassable because of the stench of the

dead animals along the road which is literally lined with them and ther is

scarcely a single train or wagon but leaves one or more dead animal, so that it

must be getting worse every day.”

One traveler described traveling down

the Humboldt

“and

crossing the desert for more than one hundred miles before reaching the

Sink…There is no grass of any consequence, the water is slippery stuff

resembling weak lye as much as anything: from the Sink to Carson River is a

distance of forty miles, the last twelve deep sand.”

Estimates put the number of travelers

who came over the trails in 1849 at around 35,000. Another 15,000 came round

the Horn, 6,000 across Panama. Numbers ran just as high for the next three or

four years; but the fever ran hottest in ’49. (Andrist estimates that tens of

thousands of travelers died by the end of the 1850s)

Andrist describes the hard work

involved:

For

mining involved more than swishing a little gravel and water around in a basin;

it was hard, back-straining work. Placer gold, the only kind really known

during the gold rush, consists of gold dust and occasional nuggets scattered

thinly through sand and gravel (a miner never called it anything but “dirt”).

To obtain the gold, it was necessary to wash a great deal of dirt, taking

advantage of the fact that gold is about eight times as heavy as sand and will

settle to the bottom while the sand is being carried oft by the water. The gold

pan, traditional symbol of the miner, was used only in very rich claims or for

testing samples of dirt to see whether they were worth working further. In

ordinary circumstances, a hopperlike device of wood and perforated sheet iron

called a cradle, or rocker, was employed in a two-man operation: while one

shoveled in the dirt, the other rocked the device and poured water with a

dipper. The dirt was washed through, and the gold was caught in settling

pockets.

After

1849, an invention called the long tom was used wherever there was a good

supply of running water. It was simply a wooden flume with water running

through it; dirt was shoveled in and sluiced through while the gold caught on a

slatted bottom. A long torn was worked by several men and could handle four or

five times as much dirt per man per day as could a cradle. That meant, of

course, that a miner had to shovel four or five times as much dirt into it as

he would into a cradle to keep it operating at full efficiency. A man usually

had to pay for what he got, even in the gold fields.

The

terrain on which the prospectors worked did little to make things easier for

them; it was usually difficult. The diggings were chiefly along the tributaries

of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, which flowed out of the Sierra

Nevada; each river, fork, branch, and creek was eventually followed by

prospectors to its source. In the lower foothills the land might be only

moderately rocky and hilly at best; near the headwaters rushing streams flowed

in the clefts of deep, precipitous gorges whose bottoms were often cluttered

with boulders and fallen rocks and choked with jackstraw tangles of dead trees.

Even under these conditions, miners persevered at the ever-absorbing task of

separating a small amount of gold from a mountain of gravel, and with amazing

energy and ingenuity constructed hydraulic works to enable them to move the

stream here or there or otherwise exploit it in their search for wealth.

One miner writes home that there are

stories of men taking in as much as $16,000 in one day, but such strikes are “once chance out of a thousand; the

average is from ½ to 2 ounces per day….I shall stay up to the mines all winter,

if I can make an ounce a day.”

In August, a miner wrote home, saying

that agriculture in N. California was “all at an end” and provisions had to be

brought from lands far away. Prices naturally skyrocketed:

“I

will just give you a summary; Salt Pork here [in San Francisco] 75 cents per

lb. at the mines $200 per Barrel. Flour $2.00 per lb. Bread at the mines one to

one half dollars per lb. Sugar at the mines $2.00 per lb. tea $4.00. Revolving

pistols woth in N. York $11.00 are here worth $55-75 dol. each. Onions 25-50

cents each. Potatoes about $30 per bushel. A ship load of the latter would

bring two hundred thousand dollars.”

Another miner described his comrades

as “the hairiest set of fellows that ever existed.”

Not only did most miners not “strike

it rich,” the gold fields could be a dangerous place. A former school teacher

wrote home in March 1852, “Seventeen dead bodies wee found on one road alone

within the last four months and no clue to the perpetrators of this wholesale

slaughter has as yet been discovered. California is yet sadly wanting in an

effective judicial and constabulary organization.”

As late as 1853, a missionary spoke

of the richness of California, but warned, “You can form no adequate idea of

the depth of sin and moral degredation to which most of the people are sunk or

rather sink themselves…There are a few however, who have not bowed the knee to

Baal.”

Still: There were stories of men

digging out gold flakes from between rocks with nothing but spoons. Near

Auburn, four cart loads of dirt yielded one lucky miner/s (??) $16,000 in gold;

and in the first days of the rush, Andrist writes, “it was not at all unusual

for a man to dig $1,000 to $1,500 worth of gold between dawn and dusk.” A man

near Angel’s Camp was hunting for rabbits. He jammed his ramrod down into the

roots of a manzanita bush, and turned up a piece of gold-bearing quartz. That

day, using his ramrod alone, he made $700. The next day, with better

implements, he made $2,000. His third day of digging yielded $7,000. Three

Germans, taking a shortcut home, struck it rich on the Feather River, taking

out $36,000 in four days, without even having to wash gravel, and what became

known as Rich Bar was soon swarming with other miners. Claims here were so rich

it was agreed they would be limited to 10 feet square. Single panfuls of dirt

were turning up $1,000 to $1,500. A company of four men made $50,000 in a

single day. By 1852, however, the rush was nearly ended, most of the great

spots having been discovered.

One miner wrote home in March 1852,

“Jane

i left you and them boys for no other reasons than this to come here to procure

a littl property by the swet of my brow so that we could have a place of our

own that i mite not be a dog for other people any longer…i think that this is a

far better country to lay up money than it is at home. if a man will…tend to

his business and keep out of licker shops and gambling houses. that is the way

the money goes with many of them in this country. thare are murders committed

about every day on the acount of licker and gambling but i have not bought a

glass of licker since i left home…i never knew what it was to leave home till i

left a wife and children…i know you feel lonsom when nigh apears but let us

think that it is for the best so to be for and do the best we can for two years

or so and i hope Jane that we shell be reworded for so doing and meet in a

famely sircal once more. that is my prayer.”

|

Sorry this is blurry; it's from an old slide turned into a picture. A stone pile at almost dead center shows where the sawmill used to be. |

*

Here’s

a short reading I provided for students, if you can use it.

James Marshall

had been born in New Jersey. He came to California after first trying his hand

at farming in Missouri. There he grew sich with fever carried by mosquitoes and

headed for healthier climates. He never made much money from his discovery.

Eventually, the State of California granted him a small pension.

Marshall

never married and died in 1885.

Henry

Bigler worked at Sutter’s Mill where gold was first discovered. Afterwards he

used to tell friends he was going “duck hunting” and look for gold on his own.

On February 22, 1849, three miles down the American River, he found an ounce-and-a-half

(worth the equivalent of $1,842 today)

“Gold fever” was always hard to resist.

In spring 1849 a prospector visiting

friends in San Francisco told all who would

listen that he had taken twenty ounces of gold out of his claim in eight

days of digging. Another fellow who caught the fever remembered his excitement:

“Piles of gold rose up before me at every step!” He saw himself in a great

marble mansion, with slaves to wait upon him and beautiful young women

competing for his love.

The

news of rich gold strikes soon swept San Francisco and the nearly deserted

streets appeared “as if an epidemic had swept the little town.” Doctors forgot

their patients and headed for the gold fields. Patients followed if they were

healthy enough. The town council canceled its next meeting and “headed for the

hills.” Sailors abandoned ships in the harbor. Even captains left their vessels

to rot. U.S. soldiers deserted, too, and officers sent to find them never

returned to their posts. (Army records indicate that 716 officers and men out

of 1,290 soon disappeared.) Farmers left crops in the fields and cows roamed

free, eating what they pleased. Ministers, students, unhappy husbands and happy

ones, a few good women, and others not so good, gamblers, and criminals of

every kind left for the mines to dig for gold or carry on their trades.

|

Abandoned ships fill San Francisco Bay. |

No

wonder they were crazy with gold fever. A claim on Feather River yielded 273

pounds of gold in seven weeks. A boy named Davenport took 77 ounces from his

claim one day ($94,556) and 90 the next ($110,520. It was said a cook in one of

the mining camps cut open a chicken and found a half-ounce nugget the bird had

pecked at and swallowed. One prospector dug down and hit a rich pocket of gold

dust and nugges, enough to fill a towel. He decided he had probably taken all

he could from his claim and “sold out” to a fellow named Lorenzo Soto. Soto

took out 52 pounds of gold from the same claim in eight days.

Chino

Tirador took so much gold out of his claim that he could barely carry it. He

then began selling gold for two silver ollars an ounce—a very poor price

indeed, The next day, Tirador discovered that other men had been working his

claim at night. So he bought a bottle of whiskey and launched a career as a

professional gambler. According to one California history, “By ten o’clock that

night he was both penniless and drunk.”

Soon

the fever spread across the nation. On September 20, 1848, the Baltimore Sun and other papers “back East” began

reporting on the incredible gold discoveries. President James K. Polk soon announced

to Congress that rich deposits of gold had indeed been discovered in

California. Men and women were now frantic to reach California and fought to

gain places on ships heading in that direction. Others could hardly wait until

spring in 1849 to set off by wagon. Half the men in Oregon gave up whatever

they were doing and headed south to the diggings. Prospectors from as far away

as Chile, China and Great Britain joined the rush. Soon trails and oceans were

covered with dreamers headed for the Pacific shores.

|

| A woman weeps as a loved one heads West, bound for California. |

Thousands

never made it. They died in storms at sea or from disease or attacks by Native

Americans along the trails. One three-year-old fell out of a wagon and under

the wheels and was crushed. Four others died on the trail when an oak tree

split in a storm and a great limb fell atop their tent.

As

always, luck shined on some and not on others.

In

those days, before television, movies and the internet allowed people to “see”

the world, the circus was a popular form of entertainment. The most amazing

experience of all was to buy a ticked and see an elephant. Now, people headed

for California told friends and relatives they were “going to see the elephant.”

In the

gold fields new towns sprang up overnight and grew rapidly. It is estimated

that 90% of the population of these towns was male. Drinking, gambling and

fighting filled the social calendar. Gamblers often got rich by cheating miners

at cards and other games of chance. One prostitute claimed she had earned

$50,000, equal to several million dollars today. Good women were rare. So one

groom charged other miners $5 simply to attend his wedding and see his young

bride. Theaters and dance halls sprang up in all the towns. A play which

included an actual female of good face and figure—or even not so good a face

and figure—was sure to sell a fortune in tickets. A female singer could expect

thunderous applause and a shower of presents after any concert.

Even

the town names tells us something about this strange new land. Some of the

best: Hangtown (where miners hanged three claim jumpers from a tree), Slapjack

(slang for “pancakes”), Whiskey, Hoodoo, Muletown, Chicken Thief Flat, You Bet,

Jacksass and Pinchemtight.

Prices

for food and equipment were always high. So most miners never really got rich.

Those who made only enough in the “diggings” to apy expenses called their work

“mining for beans.” One husband

returned home from his claim after several weeks. He was happy to have a few

ounces of gold. But while he was gone his wife had made more money just by

doing laundry for men in the camp.

|

| Headed for the gold fields, filled with hope. |

|

| Leaving the gold fields, flat busted. |

*

One of these days I’m going to

get around to writing up the Gold Rush in a more detailed story for students.

I have a reading almost ready

on the Silver Rush of 1859, in Nevada. And I do sell

materials at TpT, if you’re interested.