IF ONE PICTURE can capture the nature of war, particularly the grinding, almost always fruitless trench warfare of 1914-1918, this is probably it.

*

Last I checked, a plan to ask young women to register at 18 had been shelved.

You can usually get a good discussion going by asking students if they believe everyone would be better off if they did service in the military (or non-related government work, like hospitals, parks, age 18-20).

|

| Draft notice. |

*

Distrust of German-Americans ran strong once the United States entered the war. (Above: caricatures of a German-American defiling the flag; a German-American plotting sabotage.) It was never as virulent as the sentiment against Japanese Americans in 1941; but it had its hard edge.

Anti-German propaganda helped fuel the desire to fight.

Unfortunately, the same process often leads to the commission of atrocities on the battlefields and even behind the lines.

Unfortunately, the same process often leads to the commission of atrocities on the battlefields and even behind the lines.

In any case, not everyone was anxious to go off to war.

*

In these years, Congress passed laws to ease the path to deportation for foreign-born radicals, including labor union organizers, particularly members of the radical International Workers of the World (I.W.W. or “Wobblies”).

An I.W.W. song of that era discouraged young men from enlisting:

I love my flag, I do, I do,

Which floats upon the breeze,

I also love my arms and legs,

And neck, and nose and knees.

One little shell might spoil them all

Or give them such a twist,

They would be of no use to me:

I guess I won’t enlist.

I love my country, yes, I do

I hope her folks do well.

Without our arms, and legs and things,

I think we’d look like hell.

Young men with faces half shot off

Are unfit to be kissed,

I’ve read in books it spoils their looks,

I guess I won’t enlist.

Many Americans, in 1914, hoped the U.S. would remain on the sidelines and let the Europeans fight it out.

As Americans rang in the New Year in 1915, they worried that there might be serious trouble ahead.

Three years after the sinking of the Titanic, with the loss of 1,503 lives, a German U-boat sank the passenger liner Lusitania, with the loss of 1,198 passengers and crew.

The German government cited warnings it had posted against sailing on vessels entering a war zone. Most Americans reacted to the sinking with fury and disgust.

|

| Students should know: propaganda is designed to stir an emotional response. |

Later, an enlistment poster featured a drowning mother and child, evoking German atrocities at sea.

Oddly topical in 2019: We don’t like it when hostile foreign powers try to shape American public opinion.

President Woodrow Wilson walked a fine line in 1916, alternately trying to pressure the Germans to refrain from attacks on the high seas and still remain neutral, without making the United States seem weak.

A British newspaper mocked Wilson for sending a series of protests to Germany, after the Lusitania was sunk.

A particularly evocative anti-Wilson cartoon from 1916.

While the European powers set about destroying each other, American industry boomed.

As as often been true (1800, 1824, 1876, 1960 and 2000, the election in 1916 was extremely close. For three days it was unclear whether Wilson would win reelection or be replaced by Charles Evans Hughes.

Wilson won California by only 3,773 votes, and with victory there (13 electoral votes at the time), secured 277 electoral votes to 254 for Hughes.

A century ago, New York had 45 electoral vote, Pennsylvania 38, Illinois 29 and Ohio 24.

Texas had 20, Florida (in an era before air-conditioning, sun worship and bikinis), only 6. Even North and South Dakota had 5 electoral votes apiece.

In 1916, Wilson campaigned for reelection partly on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” A few months later, that changed.

President Wilson’s attitudes, as well as the attitudes of many Americans gradually shifted, and by early 1917, the nation was preparing for war.

Draft registration notices in multiple languages; as always, many new Americans enlisted to serve their adopted country.

(I will allow you to draw your own conclusions here.)

Once war was declared, the United States geared up to fight. James Earl Flagg produced several famous recruitment posters (below).

Flagg also urged civilians to do their part, planting gardens and increasing the food supply, so that there would be more food for the troops and for export to our allies.

Uncle Sam looks with pleasure upon a good harvest in 1917.

As was true in World War II, in World War I, the U.S. built merchant vessels and warships faster than the enemy could build them.

(It’s interesting to me to think that most ship-building operations in the United States have in recent years been moved overseas.)

I always felt students were more interested when we could humanize the people we were studying. Above, American “doughboys” admire a pretty mademoiselle. I assume, the men of

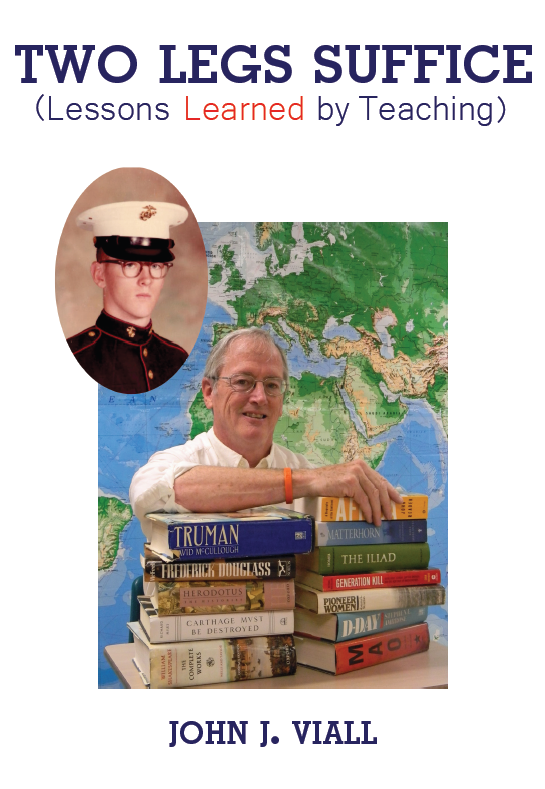

I do think students should focus on the tragic cost of any war, as show here as a mother sews stars on a pennant to represent her lost sons. (Perhaps your students are familiar with the movie, Saving Private Ryan, based on a true story—one line in a Steven Ambrose book.) I know my mother cried the day I left to join the Marines (12/28/1968). I was 19 and too dumb to even understand why.

I got lucky—despite volunteering twice to go to Vietnam—and remained safe and sound at Camp Pendleton, California. I was a supply clerk and used to tell my students I defended America with my staple gun.

American troops greeted as heroes in Paris.

One soldier who paid a fearsome price.

Sgt. Alvin York was the most decorated American soldier in the war. A pacifist, he was initially unwilling to fight; after a change of heart, he put his skills as a backwoods Tennessee hunter to good use. But after the war he never liked to talk about killing his fellow man.

America’s top ace, Eddie Rickenbacker (above), with 26 “kills.” The word “kills” has a much more powerful meaning than your students might think.

Parachutes were not in use during World War I; and on one occasion a pilot who set fire to an enemy plane watched in horror as his foe jumped out hundreds of feet in the air, hoping to land in a lake. He missed.

The first “tanks” ever to appear in combat—they were primitive machines.

President Wilson believed the United States was fighting for high ideals.

Uncle Sam takes on the true enemy. In those days, sadly, Americans knew all about lynching at home. (Leo Frank, a Jew accused of murdering a little girl was lynched in 1915.) African Americans were victimized again and again, including veterans who came home from the war, having fought for whatever high ideals it was we were fighting for. A number of particularly bad race riots also occurred in 1918 and 1919.