NOTE TO TEACHERS: I don’t know if teachers even cover the War of 1812. I did it quickly, but had success with one opening example. It was one I came across in an otherwise boring book by Marshall Smelser. He noted that France and England were both powerful, but in different ways – and could not come to grips with each other and win decisive victory. I would ask my students, “Okay, England was powerful at sea? They would be like a __.”

Students

would offer various guesses – “whale,” being most common, “barracuda,” etc.

Smelser preferred: “Shark.” A man-eater.

Next,

“France was powerful on land. They would be like a __.”

Guesses

here were more varied: “lion,” grizzly,” etc. Smelser used the tiger as

example. Another hunter of men.

Next,

you told the class the U.S. was weak on both land and sea. “We would be the

__.”

The

answer Smelser used was the “terrapin,” an edible turtle.

*

Hendrik Van Loon,

writing in 1927, explained that the two powers, France and England, solved

their dilemma “after the old and trusted habit of all big nations, by

sacrificing the rights of the small ones.”

NOTE TO TEACHERS: I sometimes threw in a quote from Thucydides: “In

fact, the strong do what they have the power to do, and the weak accept what

they must.” I tried to make it clear to my classes that the behavior of nations

changes little over time.

Van

Loon has his own take on the subject, writing, “Let me remind you here that in

the code of international relations there is no such word as affection.” (124/381)

We

always had a good discussion in my class based on the question, “What do

nations want most?”

My answer was “power,” which got you everything else. Students can give you a lengthy list of what nations want, in the process.

AS THE U.S. drifted toward war, Democratic-Republicans in Congress finally accepted a bill to authorize 50,000 additional volunteers – but refused to expand the size of the navy. In almost every public statement, by Monroe, Madison, and others, “the theme of national honor was reiterated again and again as the most compelling motive for a declaration of war.”

Unfortunately, the British ambassador was

listening to Federalists, who claimed the U.S. had no intention of fighting,

and that such talk was only political, meant to ensure Madison won reelection

in 1812.

*

March 9: A variety of issues complicated the situation. First, a series of letters by John Henry, revealed that he had been sent by the Governor General of Canada to encourage Federalist leaders in New England, should they choose to break away from the U.S. Unhappy with his treatment at the hands of the British government, Henry, an Irishman, agreed to sell the letters to the U.S. for $50,000.

President Madison revealed them in a message to Congress.

France then caused fresh trouble, burning two American ships bound for Spain with food for Wellington’s army. Calling in the French ambassador for a dressing down, James Monroe’s opening words were,

Well, Sir, it is then decided that we are going to receive nothing but outrages from France! And at what a moment too! At this very instant when we are going to war with our enemies. Remember where we were two days ago. You know what warlike measures have been taken for three months past. … We have made use of Henry’s documents as a last means of exciting the nation and Congress. … Within a week we are going to propose an embargo, and the declaration of war… to be the immediate consequences of it.

*

April 7: In an editorial in the National Intelligencer, it was

hinted that the U.S. might go to war with Britain – and France. A week later,

another unsigned editorial, penned by Monroe, called for an “open and manly”

fight, to uphold the honor of the nation. “Let war therefore be proclaimed

forthwith with England.”

*

June 1: President Madison asks for a declaration of war. The House approves on a 79-49 vote.

Federalists in Congress put forth an

amendment, calling for the war to be limited to naval operations. When that

fails, they called for a modification, to include possible measures against

France. One amendment failed – on a tie vote. The British ambassador hit on the

idea of getting Sen. Richard Brent of Virginia, “famed for his affection for

the bottle,” as Ammon put it, so drunk that he could not appear again to vote.

*

June 17: The Senate votes for war, 19-13. (24/280, 299, 302-305, 310)

NOTE TO TEACHERS: By comparison, the vote for war in 1941 was 82-0

in the Senate, and 388-1 in the House.

The Tonkin Gulf Resolution, which gave President Lyndon B. Johnson, authority

to take military action in Vietnam passed the House 416-0, and the Senate 88-2.

The resolution passed in 2002, to allow President George W. Bush to strike Iraq, passed, but in divided fashion: 296-133 in the House, 77-23 in the Senate.

*

The ships were pine-board boxes.

SEVENTY YEARS after the War of 1812 began, Charles Coffin wrote:

The United States had been a nation just twenty-five years…In sentiment the United States were not a nation. The people of the several States had no particular love for the Union; they had done nothing for it, and had little comprehension of what it had done or could do for them. (72/148)

The

United States had twenty vessels – the largest carrying forty-four guns. Great

Britain had one thousand and sixty vessels in her navy, some of them carrying

one hundred and twenty guns. The newspapers of London ridiculed the navy of the

United States, and said that the ships were pine-board boxes, while the British

vessels were built of English oak. (72/159)

One glaring issue remained the impressment

of American sailors, who were often dragged off ships, labeled “British,” and

forced to serve in Great Britain’s fleets.

Meanwhile, American shipping

interests had been badly damaged over the years, with many vessels captured. “England had taken nine hundred and

seventeen, and France five hundred and fifty-eight. The loss to Americans was reckoned

at $70,000,000.” (72/146-147)

“All this was done under pretense of

right,” said another historian, “but the Americans felt it was the right of the

highway robber.” (56/248)

*

“You have tempted him to eat of the tree of knowledge.”

Coffin also remarks on the reluctance of John Randolph of Roanoke to see Canada invaded and perhaps invite retribution from Britain – including efforts to invade the slave states and stir up racial war.

Warned Randolph:

“The

negroes are rapidly gaining notions of freedom, destructive alike to their own

happiness and the safety and interests of their masters. The night-bell never

tolls for fire in Richmond that the frightened mother does not hug her infant

more closely to her bosom, not knowing what may have happened.” (72/148)

When this blogger goes searching for another source, he finds this, from Benson J. Lossing, writing in the Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812, Chapter XI:

[Randolph] said the negroes were rapidly gaining

notions of freedom, destructive alike to their own happiness and the safety and

interests of their masters. He denounced as a “butcher” a member of Congress

who had proposed the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. He said

men had broached on that very floor the doctrine of imprescriptible rights to a

crowded audience of blacks in the galleries, teaching them that they were equal

to their masters. “Similar doctrines,” he said, “are spread throughout the

South by Yankee peddlers; and there are even owners of slaves so infatuated as,

by the general tenor of their conversation, by contempt of order, morality,

religion, unthinkingly to cherish these seeds of destruction. And what has been

the consequence? Within the last ten years repeated alarms of slave

insurrections, some of them awful indeed. By the spreading of this infernal

doctrine the whole South has been thrown into a state of insecurity. . . . .

You have deprived the slave of all moral restraint,” he continued, addressing

the Democratic members; “you have tempted him to eat of the tree of knowledge

just enough to perfect him in wickedness; you have opened his eyes to his nakedness.

God forbid that the Southern States should ever see an enemy on these shores

with their infernal principles of French fraternity in the van! While talking

of Canada, we have too much reason to shudder for our own safety at home. I

speak from facts when I say that the night-bell never tolls for fire in

Richmond that the frightened mother does not hug her infant the more closely to

her bosom, not knowing what may have happened. I have myself witnessed some of

these alarms in the capital of Virginia.”

NOTE TO TEACHERS: I retired before I ever saw this passage. If I was

still working hard in the classroom (do we ever not work hard, if we care about

our business?) I think I could adapt this slightly and use it with students.

*

“The right of the United States would be supported by the sword.”

February 7: No doubt, Tecumseh understood the power dynamics of his time. In A Popular History of Indiana, we read that he and Gov. William Henry Harrison had discussions about treaties, but they bore no fruit.

Mrs. Hendricks writes,

After

this many talks were held, but no agreement was reached, and Governor Harrison finally

said that “the right of the United States would be supported by the sword,” if

need be. “So be it,” was the stern and haughty reply of the Shawnee chieftain,

and soon afterward he drifted down the rivers in his birch-bark canoe to visit

the tribes in the southwest and to persuade them to join in the great uprising.

He told them that when the proper time came he would stamp his foot and the

whole continent would tremble. It so happened that soon after his return to the

north there was a dreadful earthquake. (91/91-92)

The New Madrid earthquake, as it is known, is actually a series of shocks, the first on December 11, in 1811, the second on January 23, 1812, and an even more powerful quake on February 7. Estimates vary, with the three quakes possibly measuring magnitude 8.1, 7.8 and then 8.8 on the Richter scale. It is said that President James Madison and his wife, Dolly, felt the tremors as far away as Washington D.C.

After the February 7 earthquake, boatmen reported

that the Mississippi actually ran backwards for several hours. The force of the

land upheaval 15 miles south of New Madrid created Reelfoot Lake, drowned the

inhabitants of an Indian village; turned the river against itself to flow

backwards; devastated thousands of acres of virgin forest; and created two

temporary waterfalls in the Mississippi. Boatmen on flatboats actually survived

this experience and lived to tell the tale.

*

Time-Life has some good details, related to the coming war. “The devil himself,” wrote one congressman, “ could not tell which government, England or France, is the most wicked.” When John Randolph begged lawmakers not to side with a tyrant, Napoleon, feeling against him ran hot.

The town of Randolph, Georgia changed its name to “Jasper.”

The American navy,

small as it might be, was, “ship for ship, as good as any in the world – a fact the Americans themselves were the last

to realize.”

*

July

18-20: The U.S.S.

Constitution had to evade an entire British squadron in a chase that lasted

for three days, to get out of Boston harbor and put to sea. Built in 1797, Paul

Revere copper-plated her hull six years later. Her towering masts “could carry

almost an acre of white canvas.” (Failed to note source.)

*

Coffin (I believe) describes the chase:

Off Nantucket one dawn, the Constitution came upon a fleet of eleven enemy ships. There was no breeze to speak of and Captain Isaac Hull had to act quickly. The water was only twenty fathoms. So he ran out the kedge anchor and a small boat carried it half a mile and dropped to the bottom of the sea “and then the sailors on the Constitution go round the windlass upon the run.” A breeze came up briefly and died “and now all through the day, through the night, the race goes on – the Shannon and Guerriere pulling with all their might.

The

master-mechanic, when he laid the keel of the Constitution; the wood-choppers of Allentown, on the banks of the

Merrimac, in New Hampshire, where they felled the giant oaks; the carpenters

who hewed the timbers, little thought how glorious would be the history of the Constitution. This was its beginning – a

race with eleven vessels trying to catch her – a hare with the hounds upon her

track. Brave men stand upon her deck. Every pulse beats high. The shot from the

Shannon do not reach them. They are

holding their own. Three cheers ring out as they whirl the windlass and pull at

the oars. All day, all night, till four o’clock in the afternoon of the second

day, the race goes on, when the Shannon,

instead of being within cannon-shot, is four miles astern…

Dark clouds in the

west hint at a storm; the Constitution

raises all sails, and “under a great white cloud of canvas, sweeps away, and

the hounds give up the chase.” (72/160)

*

August 16: General William Hull, with 2,500 men, decides to surrender Detroit to a British/Canadian/Native American force roughly half that size.

Writing decades later, Lossing placed the blame for this sorry affair on President Madison and his Secretary of War. “The blundering administration – blundering in ignorance – made [Hull] a scapegoat to bear away the sins of others – a conductor to avert from their own heads the lightning of the people’s wrath.”

Congress now set aside money for

a buildup of the army to 25,000 regular troops. A million dollars was

appropriated for purchase of arms, ammunition and stores for the army, another

$400,000 for powder, cannon and small arms for the navy. Including volunteers,

the U. S. would soon have 70,000 men under arms.

|

| General Hull surrender's his sword. |

*

“Old Ironsides” teaches the British a lesson.

August 19: Commodore Isaac Hull [no relation

to Gen. William Hull] briefly described the famous battle between the U.S.S. Constitution, later nicknamed “Old Ironsides,” and

H.M.S. Guerriere: “In less

than thirty minutes from the time we got alongside of the [Guerriere] she

was left without a spar standing, and the hull cut to pieces in such a manner

as to make it difficult to keep her above water.”

According to Henry Adams, this single

victory at sea “raised the United States in one half hour to the rank of a

first-class power.” (56/284)

*

THE HISTORIAN Coffin tells the same story, in greater detail. Hull and Captain James Dacres had known each other before the war. Coffin says they made the bet of a hat, over who would win if war came, and their ships met. Off Newfoundland, the Constitution spotted Guerriere. When the vessels closed the distance, Guerriere opened fire first, her shots falling short. Closer the British came, firing again. Hull ordered his guns double-shotted, with 32-pound balls and charges of grape. “Another broadside crashes into the timbers of the Constitution,” Coffin explains.

The

sailors are impatient. It is hard to stand silent and motionless by the

double-shotted cannon, with the splinters flying, the balls tearing everything

to pieces around them, and not to be allowed to fire. Captain Hull stands upon

the quarter-deck, calmly waiting till every gun will bear. It is the fashion of

the times to wear tight pantaloons, and his are very tight.

Finally, Hull shouts for his gun crews to blast the British.

In

the energy and excitement of the moment the captain bends low, and the

tight-fitting pantaloons split from waistband to knee. “Hull her! Hull her!”

Lieutenant Morris shouts it; and the sailors – comprehending the play on words,

that they are to do to the Guerriere

what their captain has done to his pantaloons – spring to their work with a

hurrah! Keeping up a continual roar of thunder from the double-shotted guns

Twenty

minutes, and the Guerriere is a

helpless wreck – every mast gone, gaping rents in her sides, her cannon silent.

When an American officer went aboard, he assured Captain Dacres he could keep his sword, but he would like to trouble him for his hat.

The

Guerriere was filling with water, and

was such a wreck that Captain Hull, after tenderly caring for the wounded and

removing the men, set her on fire. When the fire reached the magazine a great

wave of flame shot into the air, lifting remains of masts, spars, cannon,

anchors, ropes, and chains, which rained down into the sea, and all that was

left of the Guerriere disappeared

forever.

On August 30, the Constitution sailed into Boston.

What

commotion there was…The shopkeepers put up their shutters; the people thronging

from their houses down to the wharves; cannon thundering a salute; ladies

waving handkerchiefs from the windows; men and boys shouting themselves hoarse.

It was not only that the Guerriere

had been annihilated, but England was no longer to have things all her own way

on the sea – no longer to claim undisputed ownership of the ocean. It was the

beginning of the vindication of right and justice for the people of the United

States and, through them, for the rest of mankind.

*

October 13: An American attack into Canada, at Queenstown, near Niagara Falls, failed when only 700 men crossed. The rest of the troops refused to set foot on foreign soil. “This pattern was repeated over and over again throughout the land battles on the northern frontier – at Stony Creek, at Beaver Dams, at Chrysler’s Farm. There were men enough on the American side, but they would not fight.”

The troops heard

rumors that if they did cross into Canada they would become regulars and be

liable for five years’ service.

*

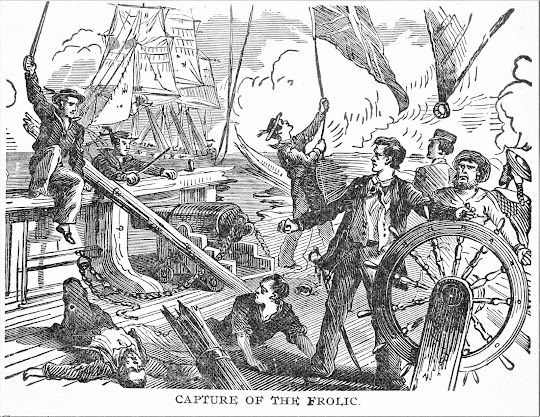

October 18: Wasp, 18 guns, falls in with seven British ships, six merchant vessels, and Frolic of 20 guns.

A

storm has made the seas rough; but the sky is now clear; and the Frolic takes in sail, evidence she is

spoiling for a fight. Captain Jacob Jones, of Wasp, notices the waves and reminds his men to fire when the ship

is going down into the trough, or else their shots will sail high. The two

ships tangle together after a few brutal minutes, most of the American fire

pummeling the enemy warship. The British crew of 108 numbers 92 killed and

wounded. Wasp has five killed, five wounded.

*

October 25: Next, the United States, 44 guns, fell in with Macedonian, also 44 guns:

The

battle began, and for half an hour there was such a cloud of smoke rolling up

from the United States that Captain

Carden, of the Macedonian, thought

she was on fire. During the time the mizzen-mast of the Macedonian falls, the main-yard is cut to pieces, the main and fore

top-masts tumble to the deck, the foremast is tottering, just ready to fall,

the bowsprit is splintered, and the rigging is cut into shreds. Suddenly the

cannon of the United States become

silent, and the British sailors seeing her sheer off, swing their hats and give

a cheer. They have beaten her, and she is trying to escape? Not quite.

The

man who fought the Algerines is only wearing his ship to take a new position.

He comes astern of Macedonian; in a

minute he will rake her from stem to stern. Captain Carden sees that he is

powerless, and the flag of Macedonian

comes down, while cheer upon cheer rolls up from the United States. In

half an hour the Macedonian has

become a wreck, while the United States

has suffered very little. (72/161-170)

*

December 29-30: Off the coast of Brazil, the British frigate H.M.S. Java, 38 guns, spots a sail. Aboard, she is carrying more than a hundred officers of the East India Service, headed for Calcutta.

“Laying like a log upon the water.”

The battle begins well for the British, at around 2:00 p.m. on the 30th. A shot from Java breaks the wheel of the U.S.S. Constitution in pieces. Captain Bainbridge rigs up a new system, pours fire into the Java, then steers away, fixes the wheel, returns, and lays alongside Java, “shooting away all three of Java’s masts, dismounting her guns, and making terrible slaughter, killing and wounding more than two hundred, while on her own deck there were only nine killed and twenty-one wounded.” (72/161-170)

(Below, the captain gives a different number for those wounded on his vessel.)

Captain Bainbridge

later describes the fight:

The following Minutes Were Taken during the Action

At 2.10 P.M. Commenced The Action within good grape and Canister

distance. The enemy to windward (but much farther than I wished).

At 2.30 P.M. our wheel was shot entirely away

At 2.40: determined to close with the Enemy, notwithstanding her

rakeing, set the Fore sail & Luff’d up close to him.

At 2.50: The Enemies Jib boom got foul of our Mizen Rigging

At 3: The Head of the enemies Bowsprit & Jib boom shot away

by us

At 3.5: Shot away the enemies foremast by the board

At 3.15: Shot away The enemies Main Top mast just above the Cap

At 3.40: Shot away Gafft and Spunker boom

At 3.55: Shot his mizen mast nearly by the board

At 4.5: Having silenced the fire of the enemy completely and his

colours in main Rigging being [down] Supposed he had Struck, Then hawl’d about

the Courses to shoot ahead to repair our rigging, which was extremely cut,

leaving the enemy a complete wreck, soon after discovered that The enemies flag

was still flying hove too to repair Some of our damages.

At 4.20: The Enemies Main Mast went by the board.

At 4.50: [Wore] ship and stood for the Enemy

At 5:25: Got very close to the enemy in a very [effective] rakeing position, athwart his bows & was at the very instance of rakeing him, when he most prudently Struck his Flag.

Had The Enemy Suffered the broadside to have raked him previously

to strikeing, his additional loss must have been extremely great

laying like a log upon the water, perfectly unmanageable, I could have

continued rakeing him without being exposed to more than two of his Guns, (if

even Them)

After The Enemy had struck, wore Ship and reefed the Top Sails, hoisted out one of the only two remaining boats we had left out of 8 & sent Lieut [George] Parker 1st of the Constitution on board to take possession of her, which was done about 6. P.M, The Action continued from the commencement to the end of the Fire, 1 H 55 m our sails and Rigging were shot very much, and some of our spars injured-had 9 men Killed and 26 wounded.